Welcome to a new issue of Reshaped, a newsletter on the social and economic factors that are driving the huge transformations of our time. Every Saturday, you will receive my best picks on global markets, Big Tech, finance, startups, government regulation and economic policy.

This week, I am looking back at the most relevant trends that emerged in 2020 in the innovation economy through the three usual lenses of this newsletter: policy, technology and finance. I will be back next week with a standard edition of Reshaped.

🎄 Do you want to make me a Christmas gift? Then, all you have to do is share this newsletter with a friend or colleague who might like it!

New to Reshaped? Sign up here!

2020 roundup

This list of topics does not include key fields like climate policy, ESG investing, green bonds, VC strategies, social media, biotech and other areas I have been covering during 2020. The reason is quite simple: emails have a limited length!

Antitrust

In the second half of the last decade, the diffused sentiment of optimism towards technology and Big Tech corporations gradually transformed into a form of criticism that is now known as “techlash” (see this article by the IFIT for more on the history of this concept). In 2020, the growing power of tech giants exacerbated this sentiment and led to a renewed antitrust effort not only in the US and the EU but also in countries like China, where precautionary policies can still be implemented to prevent tech corporations from becoming too powerful — see, for instance, the recent probe into Alibaba (Bloomberg).

In Europe, both the European Commission and individual countries like France, Italy and Germany filed antitrust suits against tech giants. Australia was also very active in that sense, while Japan will soon join Western democracies in the effort to regulate tech monopolies. However, it was in October that this global set of initiatives reached their peak with the start of a series of antitrust suits in the US. According to US regulators, Google and Facebook “have made the world worse by stifling competition, and less competition has meant less consumer choice, less privacy for Americans, less revenue for online publishers, less innovation for users” (see Axios for a short review of the suits).

These suits have the potential to reshape tech industries and business models, but it will take years to materialize. Nonetheless, fears of new accusations are already generating some effects in the sector. Big Tech companies have reduced their M&A activity; Facebook could have even sponsored the creation of rival services to prevent antitrust scrutiny (The Washington Post). This is also changing the relationship between tech corporations themselves, with new efforts to team-up in case of new accusations, like in the case of Facebook and Alphabet (The Wall Street Journal).

Internet regulation

The end of lax antitrust in the US has only partially been paired by effective internet regulation. The OECD is late in delivering actionable guidelines on digital taxes, which has pushed individual countries like France to act independently. At the same time, the EU is torn between ambitious regulatory schemes and the need to develop its own digital champions. The former has finally taken shape with the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act, while the latter is still the continent’s weak point. As I wrote many times in this newsletter, regulation can turn out to be incumbents’ best friend as it creates barriers to entry and sets clear expectations that reduce the need to invest in innovation.

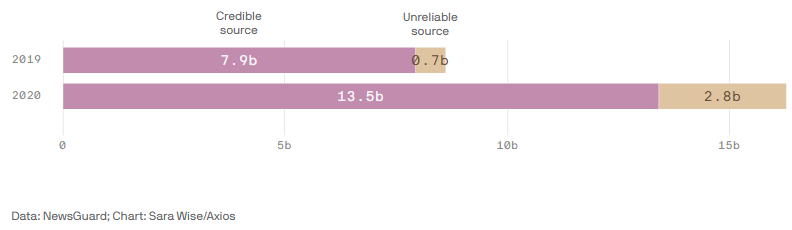

The most relevant success for internet regulation in 2020 was probably achieved in France, Australia and the UK, where tech companies will have to pay media outlets to feature news in their platforms. More recently, some form of regulation has emerged in cryptocurrencies (see The Verge for more on the US proposal). In 2021, due to the shocking SolarWinds hack in the US, we could expect a greater focus on cybersecurity by regulators. I am more sceptical about any improvement in misinformation and hate speech regulation, a crucial topic for the future of social media platforms. This year, unreliable sources got more traction than in 2019 (see chart below), a trend that should worry policymakers, tech companies and traditional media. See also Marco D’Eramo’s contrarian piece on the New Left Review about “the monopoly on legitimate lying”.

Space tech

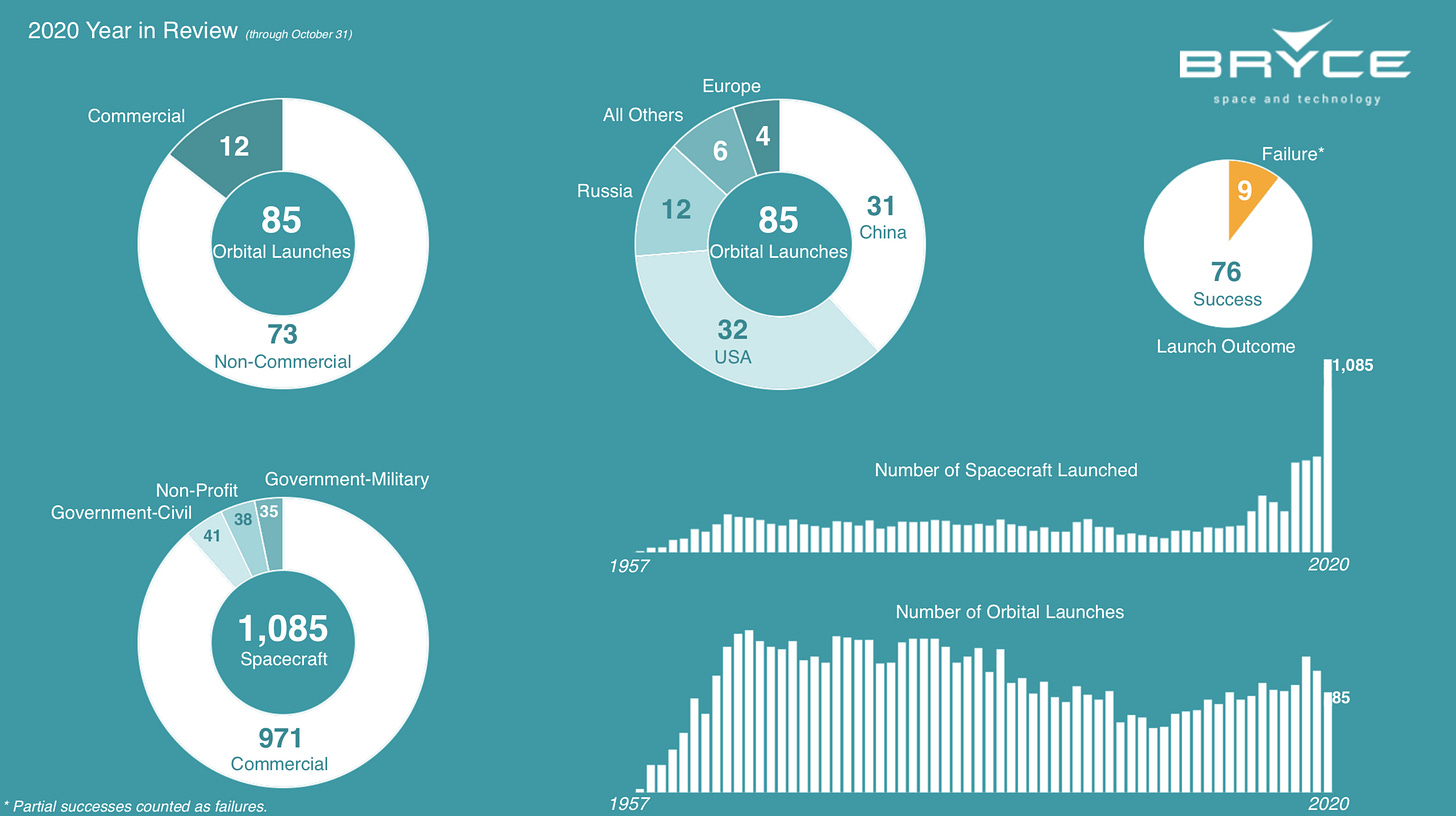

Investments in space technologies continue to increase. According to Bryce, in 2019 they reached the record amount of $5.7 billion, with VCs accounting for 71% of them. In 2020, total investments could have surpassed $6 billion, with states actively contributing through grants and acceleration programs worldwide. At the same time, the number of launches reached an all-time record of 1,085 spacecraft (see picture below). Technological advancements in both hardware (launchers) and software (AI-powered applications) are contributing to a significant reduction in spacetech costs. At the same time, the emergence of the smallsat segment aiming at the creation of ELO constellations of satellites is a positive factor for the development of downstream applications that range from consumer services to better monitoring of climate change effects on the planet.

Climate tech

Investments in climate technologies are growing at sustained pace since 2017 (see chart below). Partial data for 2020 show a record year for investments in this sector. The alignment between public and private interests has never been so strong, which makes investors believe it will not turn out as it did during the last cleantech bubble (2005-2009). An excellent MIT study back in 2016 concluded that “the VC model is broken for the cleantech sector, which suffers especially from a dearth of large corporations willing to invest in innovation”. Technological advancements and new instruments of climate finance can pave the way for a golden age of climate tech and reduce technology prices in a wide range of sectors beyond power generation.

Artificial intelligence

It was a very particular year for AI research. On one hand, many successful AI projects were disclosed — from OpenAI’s GPT-3 to DeepMind’s AlphaFold 2 — and received widespread interest. On the other, many in the sector fear that AI’s ambitions are still too big and far from reality, which could lead to a new AI winter (see Reshaped #23). In particular, one of the biggest concerns is about the centralization of AI research in Big Tech corporations (see Wired for a review of its negative consequences), which limits entrepreneurship in this field. In addition, according to Nathan Benaich and Ian Hogarth’s State of AI Report, AI research is mostly closed source, as “only 15% of papers publish their code, which harms accountability and reproducibility in AI”.

Not to mention research about ethical AI, a global effort that fails to attract enough investments and to deliver the expected results. The firing of Timnit Gebru by Google (see The Washington Post) unveiled the many contradictions that still populate this area of research and the price to pay for the big role played by private companies in it. However, the urgency to provide answers to critical questions is real. As pointed out by Pratyusha Kalluri on Nature, it is fundamental to broaden the subjectivity of AI systems to include people that are currently excluded from it.

It is not uncommon now for AI experts to ask whether an AI is ‘fair’ and ‘for good’. But ‘fair’ and ‘good’ are infinitely spacious words that any AI system can be squeezed into. The question to pose is a deeper one: how is AI shifting power? […] In my view, those who work in AI need to elevate those who have been excluded from shaping it, and doing so will require them to restrict relationships with powerful institutions that benefit from monitoring people.

Semiconductors

The chip industry was probably the most interesting sector to analyze in 2020. The year started with the renewed competition between Intel and AMD in the CPU segment and the excellent performances of Nvidia in the new GPU niches (AI in particular). Soon afterwards, however, many downstream tech giants announced the release of their own chips (The Wall Street Journal). Apple, in particular, left most tech analysts astonished at the announcement of its M1, a high-performance chip that will gradually replace Intel CPUs from the Mac product line (see Reshaped #40).

Now that Apple, Google, Amazon and Microsoft joined the chip race, semiconductor companies will have to reinvent themselves. In this process, AMD seems well-positioned to target critical niches like FPGAs — as the acquisition of Xilinx demonstrates — while Nvidia is aiming at expanding upstreams through the acquisition of the chip design company Arm. This scenario and the need of Intel to restore its dominance in the industry (the stock fell by 20% since the start of the year) will probably translate into a very interesting 2021 for the chip sector.

Electric vehicles

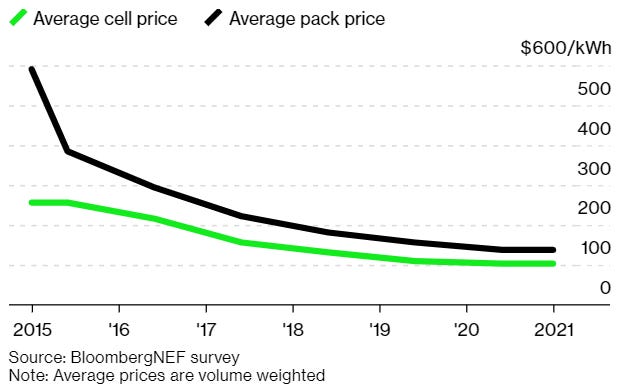

There are two trends that explain the renewed optimism about electric vehicles. First, the shape of the cost curve for lithium-ion batteries is declining (see chart below). In a few years, battery pack prices are forecasted to reach the critical $100/kWh threshold (down from $137 in 2020) to rival gasoline and diesel-powered cars. Second, there are promising innovations in the battery landscape that could accelerate adoption and make it more sustainable in the mid-term (see Reshaped #44 for more on the solid-state lithium-metal batteries announced by Quantumscape).

This translated into an incredible year for EV stocks. Tesla is up 669% with respect to the beginning of the year, with a market cap of almost $630 billion. At the same time, many EV startups have gone public through SPAC acquisitions despite being still far from revenue generation (see Reshaped #37 for more on that). This positive trend has attracted new players: this week, Reuters reported that Apple is planning to enter the EV market by 2024 leveraging on new disruptive battery technology. Apparently, Tim Cook once refused to acquire Tesla when Elon Musk was still struggling to make it excel at operations.

IPOs

Many successful tech IPOs were realized in 2020. The pandemic froze access to public markets in the first half of the year (mainly Q1) when uncertainty was widespread in almost all sectors. The excellent performances of tech stocks since the end of March quietly opened a small IPO window in June (ZoomInfo) and July (Lemonade). This led to two series of IPO rushes in September (Snowflake, JFrog, Unity, Palantir, Asana) and December (DoorDash, C3.ai, Airbnb, Wish). Airbnb, one of the big losers in the first part of the year with a private valuation that dropped from $31 to $18 billion, went public with a public valuation of $47 billion. See Crunchbase for a recap of the most relevant IPOs of the year.

Airbnb — a vacation platform that went public in the midst of a pandemic that made tourism almost impossible — is the perfect example to show both the resilience of digital business models in front of exogenous shocks and the disconnect between markets and the real economy. A movement of ideas and initiatives in favour of the latter led to the creation of Eric Ries’ Long-Term Stock Exchange and to a wave of criticism about the standard IPO process. This week, the US SEC approved a proposal by the NYSE to allow direct listings not only to sell existing shares but also to raise new capital (The Wall Street Journal). This is a convenient alternative to traditional IPOs and a major blow for investment banks, which profit from them.

This was also the year of SPACs (for more on SPACs, see Reshaped #25). Blank check companies led by famous investors and entrepreneurs brought to public markets a vast amount of startups through M&A deals — with a special focus on electric vehicles and other early-stage sectors where revenue generation is still an exception. In 2020, SPAC proceedings accounted for about a quarter of the total (see chart below) and the trend will probably continue also in 2021 with the new direct listing rules.

Tech stocks

Tech stocks had an incredible year, partially driven by the effects of the pandemic on their business and financial performance. Low interest rates drove capitals in stock markets, where the choice between value and growth stocks could hardly be described as such. Value stocks are affected by a worrying disease: expensive, low yields. In this scenario, we could say that technology companies have benefited from an additional form of monopoly power, being an almost essential feature of investment portfolios. These factors all together pushed tech stocks to record highs (see chart below). Some see this rapid growth as very far from the fundamentals of the sector and describe this situation as similar to the dot-com bubble — but I am very sceptical about that (see Reshaped #29).

As we approach the post-pandemic world, some of these tech companies will have to reinvent themselves to maintain their growth pattern and meet investors’ expectations. Zoom — probably the biggest winner in the world economy in 2020 — is going to expand its services to include other productivity tools (The Information). Other companies will probably follow Slack and give up some of their freedom in order to survive in a sector that is going to become even more concentrated in the near future. Looking at stocks at large, the pandemic had huge effects on investment strategies and rewarded cautious investors more than contrarians. As John Authers writes on Bloomberg, this was a bad year for contrarian investing — and 2021 could follow the same path.

The big picture

I am leaving you with a short and very partial list of books I enjoyed reading this year (limited to those published in 2020).

Thomas Piketty, Capital and Ideology (Harvard, 2020)

Danny Cullenward & David G. Victor, Making Climate Policy Work (Polity, 2020)

Carissa Véliz, Privacy is Power: Why and How You Should Take Back Control of Your Data (Penguin, 2020)

Isabel Wilkerson, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents (Penguin, 2020)

Lisa Adkins, Melinda Cooper & Martijn Konings, The Asset Economy (Wiley 2020)

Steve Vanderheiden, Environmental Political Theory (Polity 2020)

Lee Vinsel & Andrew L. Russel, The Innovation Delusion: How Our Obsession With the New Has Disrupted the Work that Matters Most (Penguin 2020)

Matthew C. Klein & Michael Pettis, Trade Wars Are Class Wars: How Rising Inequality Distorts the Global Economy and Threatens International Peace (Yale 2020)

Thanks for reading.

As always, I am waiting for your opinion on the topics covered in this issue. If you enjoyed reading it, please leave a like (heart button above) and share Reshaped with potentially interested people.

Have a nice weekend!

Federico