🌌 Reshaped #40

Mission-driven... bubbles, Apple M1, hydrogen economy, Biden's tech policy, development finance and much more

Welcome to a new issue of Reshaped, a newsletter on the social and economic factors that are driving the huge transformations of our time. Every Saturday, you will receive my best picks on global markets, Big Tech, finance, startups, government regulation, and economic policy.

This week, I am shortly delving into the relationship between bubbles and urgency in climate innovation. It is only the starting point of a series of analyses I will post in the upcoming issues. Your early feedback is truly appreciated!

Please, take a moment to share this newsletter with your network!

New to Reshaped? Sign up here!

Bubbles and urgency in innovation missions

Bubbles are one of the common traits of the innovation economy. Optimal allocation of resources and perfect rationality — both derived from neoclassical economic theories — mean that the iterative, error-prone innovation process that fosters the innovation economy is not fully rational and should be avoided. In this scenario, innovation could only be sustaining: disruption is an exception coming from the outside. However, endogenous growth theories argue the opposite: innovation stems from the development of human capital and internal R&D processes — that is, from the inside of the economic system.

The innovation economy relies on this suboptimal allocation of resources to generate technological standards. Hence, bubbles are totally natural in a speculation game in which investors back different routes to solving a problem or meeting market needs. If there is no dominant technological standard, the misproportion between valuations and the NPV of future cash flows of any asset class can be outstanding: indeed, cash flows can be zero if a technological solution fails to stand out as dominant (or at least valuable) in the market.

But what happens when innovation is driven by broad, public-oriented missions, heavily financed by government spending? Does speculation still play a vital role? If we look at the past, the answer is that yes, it does. The post-war tech revolution in the US took advantage of government intervention both as a market shaper and purchaser. However, this is not perfectly adaptable to mission-driven innovation aimed at facing the climate emergency, which is characterized by a new dimension: urgency. (Notice that this could be applied to the healthcare emergency as well.)

Differently from the past, we urgently need new technologies to cut emissions, make energy systems more sustainable and efficient, decarbonize the economy, and improve carbon capture and storage. The urgency to find new standards, however, might distort the innovation process in many ways, leading to suboptimal results. This includes various areas of concern:

What happens if sustainable finance actors end up investing in the wrong solutions, with negative long-term consequences for climate-oriented funds?

How do we prevent governments from picking winners to make the transition easier and faster?

How do we prevent early signals of bubble-bursting from panicking investors as it happened in the last greentech bubble in the 2000s?

Biden’s climate agenda might be the missing link between global governments committing to bold green policy and investors pouring money in the sector (for more on green-focused VCs, see my last issue). This is why, in the upcoming issues, I will dedicate more space to the new waves of technological innovation that are emerging in the fight against climate change. In doing so, I will try to answer these questions to identify different scenarios for greentech ventures and investors. If you have any comments or recommendations, leave a comment below!

The state

Antitrust

There are many question marks around Joe Biden’s approach to technology and antitrust. During the presidential campaign, he has been riding the techlash wave, distancing himself from the strict ties between Obama and Silicon Valley elites. He announced stricter privacy regulation and a novel approach to misinformation, starting from revoking Section 230. According to The New York Times, chances are Biden will continue to pursue aggressive antitrust scrutiny, targeting Amazon, Apple, and Facebook similarly to how the DOJ has already done with Alphabet.

However, Biden owes a lot to tech companies. He “raised over $25 million from internet companies” during his campaign, which was extremely popular among tech executives (MIT Technology Review). According to Wired, about 95% of employee contributions from six major tech companies went to Biden. In addition, tech policy might not be among the top priorities of the new government, which will have to face pressing challenges such as the healthcare emergency, climate change, and economic recovery.

Finally, antitrust enforcement is hard. Breaking up tech giants means engaging in an enormous effort to rebuild fairer systems. In a recent essay, Lizzie O'Shea provides a fresh perspective on that issue (The Baffler).

Moreover, breaking up big companies can work to preserve certain forms of commerce that remain exploitative of workers, or to avoid policies that require public investment in digital infrastructure, or alternatives like socialization or nationalization. Many antitrust thinkers idealize small business and tend to harbor nostalgic visions about the importance of markets. But there is a case to be made that scale and centralization bring about efficiencies and the potential for economic planning, both of which could be oriented toward the common good through public ownership.

Meanwhile, in Europe, antitrust authorities accused Amazon of anticompetitive practices towards its third-party sellers (Financial Times). Amazon would exploit its platform advantages to identify popular products to replicate and sell at lower prices. It would also use the “buy box” function to promote its own products to the detriment of other sellers. Being an ex-post antitrust case, it will take years to prove any of these accusations — the same applies to Google in the US — but it will prevent new anti-competitive behaviors from emerging.

Tech regulation moves at a much faster pace in China, where authorities forced Ant Group to postpone its record IPO. This is having major effects on the local ecosystem, dominated by Tencent and Alibaba (Yahoo Finance). Anti-monopoly enforcement here has the chance to play an easier ex-ante role, which could give China an edge in the global tech race. Chinese authorities might reverse the consolidation of the domestic tech industry, characterized by aggressive acquisitions (see picture below), and break up rising monopolies.

Industrial policy

In the US, industrial policy is emerging as a vital instrument to counterbalance the Chinese rising power. However, as pointed out by Robert D. Atkinson in a recent ITIF report, the US has no clear innovation policy system — despite its advanced business and regulatory environments.

There is no national, coordinated innovation policy system in the United States. While some nations have developed national innovation strategies (e.g., Germany, Sweden, and Finland), the United States generally has not. This reflects in part a belief that innovation is best left to the market, and that the role of government, to the extent there is one, is to support “factor inputs,” such as knowledge creation and education.

The report recommends strong measures to foster innovation policy in areas like R&D, knowledge flows, and human capital. This includes allowing high-skills immigrants to live and work in the country — they have founded “from 15 to 26 percent of new companies in the U.S. high-tech sector over the past two decades”.

At the same time, in the UK, regulation seems to be at the core of the government agenda. The National Security and Investment Bill will provide the government with the power “to block foreign takeovers of UK firms if they threaten national security” (BBC). The bill will align the UK with other European countries like Germany and France, which have already implemented similar measures to safeguard domestic companies. In addition, the UK government also announced that, within five years, climate risk disclosure will become mandatory for large companies and financial institutions, consistently with the goal of going carbon neutral by 2050 (The Guardian).

The markets

Semiconductors

With a virtual event, Apple announced the release of the M1 chip, specifically designed for its Mac product line. The chip is based on ARM architecture and is going to be manufactured by TSMC. It will gradually replace Intel processors from the Mac, as already happened in mobile devices. Technically, M1 combines various technologies into a single System on a Chip (SoC): it includes an 8-core CPU, an 8-core GPU (up to), a 16-core neural engine that enables faster ML performances, and a dedicated RAM memory. The integration of these components allows for better performances and lower energy consumption.

In his analysis, John Gruber claims that battery life is the real advantage for Apple, which was already in a positive trajectory in terms of performance with its A-series. This is clearly shown in the chart below, taken from the excellent analysis published on AnandTech, which concludes that “there simply was no other choice but for Apple to ditch Intel and x86 in favor of their own in-house microarchitecture — staying par for the course would have meant stagnation and worse consumer products”. The process that led to M1 is nicely described by three executives in an interview for The Independent, which also explores the reasons behind that simple name.

What about Intel? The chip giant is facing growing pressure from AMD in the market for PC processors. In addition, the semiconductor industry is rapidly consolidating around its major players, but this race for acquisitions has only benefited Nvidia and AMD, which are expanding their product range to AI and server chips respectively. At the moment, however, M1 is not a huge market threat for Intel: according to Pierre Ferragu, Apple accounts for 4% to 5% of Intel’s revenue (Cnet). There are little chances that, in the near future, other computer manufacturers will vertically integrate the design of their own chips.

Energy

According to the latest IEA report on renewables, the performance of renewable energy stocks (equipment manufacturers and project developers) remained strong despite the pandemic. Wind and solar, in particular, had excellent performances in Q3, while utilities dropped as a result of the lower demand for energy.

Wind turbine and solar manufacturers recorded significant declines, with many companies recording negative EBITDAs in the first half of the year as revenues temporarily fell. However, the stock prices of major wind and solar companies have rebounded, reaching all-time highs owing to strong order backlogs indicating growing demand and healthy business over the medium to long term.

This resilience is good news for industries and policymakers, as both need renewables to scale to meet their climate neutrality goals. To make the energy transition feasible, investors are focusing on potential applications of hydrogen (for a primer on the hydrogen economy, see this article on Scientific American). Despite being bubble-prone, hydrogen as a source of energy might be among the priorities of Biden’s climate change program, which makes private investments more attractive.

California is notoriously testing hydrogen to power local mobility, even if many fear it could only be applicable to trucks, buses, and airplanes. AirLiquide “is building a $150 million plant outside Las Vegas that will turn biogas from decomposed organic waste into hydrogen, which it plans to sell in California” (The New York Times). A new report by the FCH UJ forecasts an ambitious scenario in which hydrogen accounts for 24% of the final energy demand by 2050, generating more than five million jobs (see picture below).

The study does not ignore the high costs related to the production of green hydrogen. Cost reductions will be fundamental to apply hydrogen to a large enough range of fields. To that end, a report by the Hydrogen Council estimated the breakeven costs at which hydrogen application becomes competitive against low-carbon alternatives in each segment (see picture below).

The slow reduction of these costs and the difficult path to establishing policy and technological standards are major areas of concern. Andreas Kluth imagines a realistic scenario in which hydrogen plays a pivotal role to compensate for renewables’ inner fluctuations; their excess would be used to produce green hydrogen sustainably (Bloomberg).

We can electrolyze the hydrogen whenever we have excess sun or wind. As Liebreich predicts, we will then store it in massive underground caverns near the central nodes of our power grids, where it can be fired up at short notice during lulls in direct electricity generation. Hydrogen is thus the plug-in technology to make the overall project of electrification and decarbonization possible.

The speculators

Venture capital

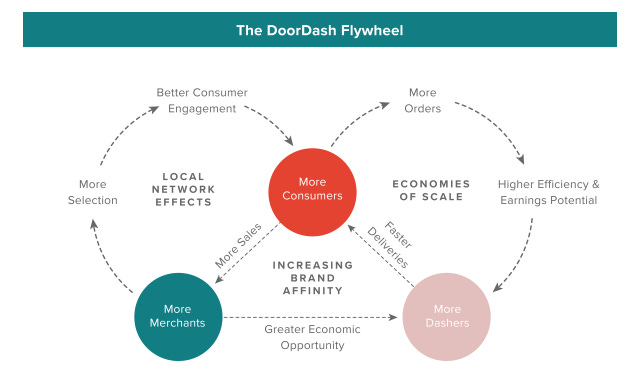

The pandemic had a positive impact on delivery companies. Nuro, an autonomous delivery startup, raised a Series C round worth $500 million at a $5 billion valuation. Meanwhile, Doordash filed for its upcoming IPO in the NYSE despite net losses (The Verge). The food delivery company, together with Lyft and Uber, successfully supported pro-gig Proposition 22 in California, which will allow it to treat drivers as contractors instead of employees. Similarly, Airbnb is ready to go public next month; however, as reported by The Information, it would be also considering listing on Eric Ries’ Long Term Stock Exchange in 2021.

VCs tend to put their money into food delivery companies because of their perceived growth potential, especially during the pandemic. However, these companies have continued to lose money during 2020, despite the surge in demand. The typical growth model of delivery startups is exemplified in the picture below, which applies not only to Doordash but to the entire sector. However, this overly exemplified model misses the crucial point: delivery companies have to fit into a predetermined system they have few chances to control. My perception is that the “myth of future glorious efficiency”, as Shira Ovide calls it, is false because these platforms only operate downstream: in the internet economy, efficiency is a function of systems control.

Meanwhile, SoftBank Vision Fund has recovered from last May’s shock (see my past issue on that topic). Masayoshi Son, supported by Elliot Management, had to review his investment strategy and sell promising companies — it could also sell Boston Dynamics to Hyundai (The Telegraph) — while changing the fund’s leadership team (CNBC). It is too early to see a signal of discontinuity from the hazardous choices of the past.

Stocks

Global stocks reacted positively to the announcement that the COVID-19 vaccine developed by Pfizer and BioNTech was 90% effective in Stage III tests (Barron’s). More specifically, the announcement caused a surge in value stocks, largely depressed by the pandemic, and a drop in growth stocks. More than a victory for value stocks, which continue to suffer from low yields, it was a sign of how fast they can reverse the consequences of the pandemic, at least in equity markets. On the other hand, the Nasdaq fell by 1.5%.

Investors have been rewarding the growing relevance of tech-driven stocks during the initial phase of the pandemic; the vaccine could naturally reduce this relevance as well as market valuations. Of course, the market fundamentals of tech companies remain the same. It is hard to imagine a drop in cash flows due to a tech-averse, revived global economy. Some bubbles might burst and institutional investors might rebalance their portfolios, but the stock advantage gained by tech companies seems to be a long-term trend with few chances to be reversed.

The big picture

In a new post on the LPE blog, Vanessa Ogle explores the “connection between decolonization and the expansion of tax havens and tax haven business during the 1950s and 1960s”. According to the author, Western companies continued to enjoy some benefits even after the end of decolonization processes, with the support of local corruption and the increased mobility of global capital.

Fear of expropriation, limits placed on the repatriation of profits, and restrictions on foreign activity in key strategic resource industries led investors to think twice about the precise legal form of a business presence on the ground (a branch, a subsidiary, a joint-venture, for example). Rather than sink funds into cumbersome and difficult to liquidate brick and mortar trappings, increasingly many investors preferred portfolio investment. Foreign investment in stocks and bonds gradually outstripped direct investments by the 1970s. Decolonization therefore became part of a much broader transformation of global capitalism, one that rendered capital more mobile.

Development is at the core of Lorena Cotza’s analysis of the dark side of development finance (OpenDemocracy). Development banks have a fundamental role to play to reverse the asset privatization trend of the last four decades, but they need to distinguish themselves from the financial industry as a whole.

Human rights abuses and lack of meaningful consultation are a common feature of many of the so-called “development projects”. Human rights defenders, civil society and local communities all over the world have been denouncing the inherent, structural problems of the current development model for years. Yet, banks keep burying their head under the sand, failing to recognise these problems and to address them.

I am leaving you with some reading recommendations:

On Real Life, David A. Banks analyzes the emergence of the subscriber city, which he perceives as aimed at “making money from restricting and provisioning access, not providing a service”. Very interesting read.

On the MIT Technology Review, Will Douglas Heaven explores the replication problem of AI research, dominated by tech giants.

On Nature, Heidi Ledford examines the reasons behind falling COVID-19 death rates.

A recent paper explores “the impact of venture capital ownership beyond the IPO listing on important consequential, corporate decisions in a firm's lifetime, including time to dividend initiation”. The results are quite surprising.

Thanks for reading.

As always, I am waiting for your opinion on the topics covered in this issue. If you enjoyed reading it, please leave a like (heart button above) and share Reshaped with potentially interested people.

Have a nice weekend!

Federico