🌌 Reshaped #29

Globalization and inequality, algorithmic colonization, Big Tech price discrimination, financial bubbles, tech IPOs and much more

Welcome to a new issue of Reshaped, a newsletter on the social and economic factors that are driving the huge transformations of our time. Every Saturday, you will receive my best picks on global markets, Big Tech, finance, startups, government regulation, and economic policy.

This week, I am mainly describing the aggregate picture emerging from the state of the innovation economy. Scroll down to The big picture for some interesting articles on the link between globalization and inequality and the impact of Western technologies on African societies.

Please, take a moment to share this newsletter with your network!

New to Reshaped? Sign up here!

The state

Mission-oriented innovation

There have been intense debates among Western leaders and thinkers on how to counterbalance the power of a planned economy like China in the long term. The mantra that free markets are more efficient seems less convincing than in the past, especially now that tech giants face opposite faiths — state support in China and (very appropriate) antitrust scrutiny in Europe and the US. This is why a bigger role of the state in upstream processes like research and development is now considered as a bipartisan, reasonable strategy for Western countries.

Such a bigger role on the upstream has strong consequences on the downstream in three main ways: it provides a direction for research and development along the entire value chain; it functions as a “soft regulatory body” for new exponential technologies like AI; it influences the shape of the market and the industrial actors that will constitute it — for instance, creating space for new entrants to prevent an oligopoly.

These are the lenses with which I am reading the US government announcement regarding “more than $1 billion in awards for the establishment of 12 new AI and QIS research and development (R&D) institutes nationwide”, focused on the advancement of AI and quantum computing technologies.

The Trump Administration is taking strong action to ensure American leadership in the industries of the future—artificial intelligence (AI), quantum information science (QIS), 5G communications, and other key emerging technologies that will shape our economy and security for years to come. […] The establishment of these new national AI and QIS institutes will not only accelerate discovery and innovation, but will also promote job creation and workforce development. NSF’s AI Research Institutes and DOE’S QIS Research Centers will include a strong emphasis on training, education, and outreach to help Americans of all backgrounds, ages, and skill levels participate in our 21st-century economy.

This form of state intervention on the upstream is very beneficial to the market economy, as many past examples have shown — we could draw a line connecting Apple’s current record market cap and the huge state spending on ICT decades ago. The announcement makes it clear that this initiative is perfectly in line with the US capitalist economic structure and that many private companies (including Big Tech corporations) will be part of it.

Importantly, these institutes are a manifestation of the uniquely American free-market approach to technological advancement. Each institute brings together the Federal Government, industry, and academia, positioning us to leverage the full power and expertise of the United States innovation ecosystem for the betterment of our Nation.

A final remark, in case you missed it: due to its state of health, Shinzo Abe was forced to resign as the Prime Minister of Japan. For a brief review of his economic policy, known as Abenomics, see the column by Daniel Moss on Bloomberg.

Antitrust

If I had to recommend someone’s writings on monopoly power and antitrust, I would surely suggest Barry C. Lynn’s. His new book, Liberty from All Masters. The New American Autocracy vs. the Will of the People, comes out in a month. Meanwhile, we can enjoy his latest piece on Harper’s, in which he explains how Big Tech companies came to control the economy through price discrimination and monitoring technologies. I am now focusing only on the former, as I have already written about the mechanics of surveillance capitalism in past issues.

After a review of how tech companies managed to build business models and develop pricing tactics based on micro-targeting — on both the buyer and the seller side — Lynn claims that this form of price discrimination has removed the very basic metric that makes a capitalist economic system free in its structure. In his own words, “prices play a major role in making the public the public”.

Markets are not only where we exchange goods and services. Well-structured markets are also one of the primary institutions providing that most basic stuff of democracy: trustworthy information about potentially dangerous concentrations of economic and political power. […] The danger of price discrimination is not merely that it grants a monopolist the ability to pick and choose winners and losers. It is not merely that it grants a monopolist the ability to manipulate commercial interactions to extort money and political favor from those who rely on them to get to market. The problem with personalized discrimination is that even as it empowers the masters of these corporations to atomize prices, it atomizes society at the same time.

This is one of the core aspects of modern monopoly power and one of the reasons behind the idea that breaking up tech companies is just a small (if relevant) piece of modern antitrust policy. Furthermore, the link between micro-targeting — and the behavioral patterns it generates — and the atomization of society is a useful addition to modern industrial organization theories. In particular, it helps to explain why it is so hard for political forces worldwide to produce economic policies that are at the same time ambitious and broadly shared.

Atomization creates a permanent “scramble for offers” that puts individual interest above all other metrics and favors the further strengthening of surveillance giants that can fulfill immediate needs in the most convenient way. It is not a case if, as a typical justification for their power, Big Tech leaders often make use of consumeristic reasoning that is hard to publicly deflate. Take a look at Asher Schechter’s interview with David Dayen on ProMarket for more on that.

As a final suggestion, I also recommend you to read the latest piece by Nick Romeo on The New Yorker, which explores how the US can take the European Union as an example for regulating Big Tech.

The markets

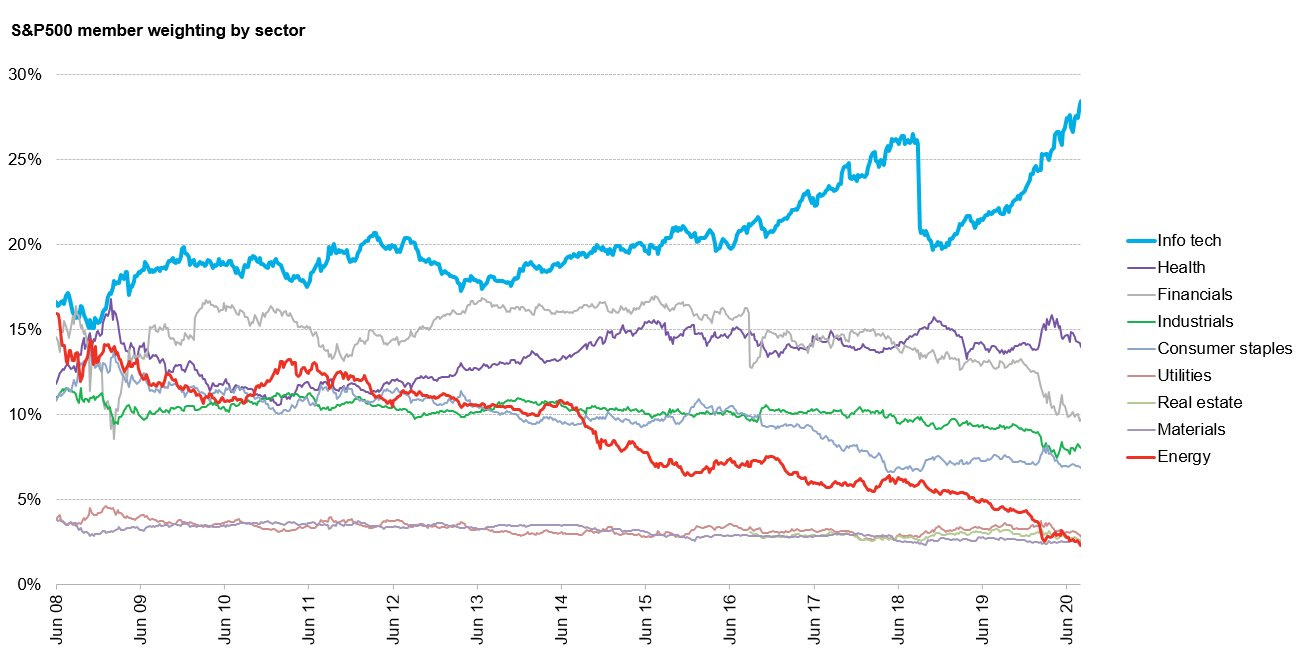

Tech companies are on fire. Their share of the S&P500 is increasing exponentially (see chart below by Bloomberg’s Nat Bullard, discovered thanks to Azeem Azhar) and more and more IPOs are scheduled to ride the enthusiasm wave (see The speculators for more on that). The current state of tech is quite clear: from Big Tech to emerging startups, the sector is focused on the sustainability of business models through the creation of new sources of recurring revenues. In times of trouble for traditional businesses, tech companies have the chance to enter new markets and differentiate their offer.

I already mentioned the relevance of the forthcoming service bundles for Apple’s $2 trillion market capitalization (see the last issue). But it also applies to Amazon, which just announced Halo, a screenless fitness band paired with a subscription-based application that monitors someone’s health through 3D modeling and voice tracking (The Verge). The healthcare and fitness sectors are extremely attractive for both incumbents willing to enter new businesses and new entrants trying to attract the flow of money that is moving from generic to sector-specific investments.

This impacts also adjacent sectors: some days ago, Verily (former Google Life Sciences, now part of the Alphabet group) announced the launch of a new insurance service company called Coefficient, aimed at offering stop-loss insurance (The Verge). Being linked with Google, Verily has faced many data governance issues in the last months, especially after the launch of the Project Baseline in collaboration with the US government (EFF). The fear that Big Tech giants could start a mass monitoring process of healthcare information is a very current topic.

A final update on the TikTok saga with three news you cannot miss. On Monday, TikTok sued the US government because of the ban ultimatum; an eventual win could give the company more time to find an acquirer. On Wednesday, TikTok CEO Kevin Mayer resigned after less than three months in charge (The New York Times). Finally, on Thursday the coalitions of potential buyers became clearer. On one hand, there is Oracle and its willingness to enter commercial business segments; on the other, there is an alliance between Microsoft and Walmart (Axios). The latter would have a chance to further improve its e-commerce services to challenge Amazon — ironically, through the exploitation of Microsoft Azure cloud services.

The speculators

As anticipated above, the current state of the markets is opening new IPO windows that would have been unexpected some months ago, at the beginning of the pandemic. The list of companies that are planning to go public includes Airbnb, Palantir, Ant Financial Services, Snowflake, Asana, Unity Technologies, JFrog, and Corsair Gaming. The common element that links them all? They are tech startups, of course. Their resilience in times of global economic troubles has generated such a FOMO effect on tech stocks that the traditional IPO process seems to be too complex to sustain the wave. This is the main reason why we have a SPACs boom right now — the value of SPACs year-to-date is estimated at about $30 billion, far above the $13 billion total value in 2019.

Of course, this extreme level of financial speculation comes at a cost. Hedge funds have profited from the suffering of traditional brick-and-mortar companies, with mortgage patterns that some practitioners have defined as a sort of “The Big Short 2.0” (The New York Times). Curiously, some of these profits are reinvested by those funds in tech securities, giving rise to an extract-and-reinvest loop that is reshaping local and global economies.

Now, the question that many are asking is: are we in the midst of a new speculation bubble? On one hand, the pattern is similar to the dot-com bubble, at least on the investor side, where institutional and retail investors are eager to invest in tech stocks. However, this time the hype follows different mechanics. The dot-com bubble was based on the naive idea that tech startups could successfully sustain increasing competitiveness while turning to profitable business models in a short time frame. The lack of a profitable path to economic success eventually made the bubble burst, since it removed the basic element that was sustaining the bubble: faith in tech startups as the new, dominant economic actor. Investors’ naivety coincided with overrating the potential of these actors as a mainstream investment opportunity.

This time is different. We saw the power of Big Tech companies during the pandemic. We are prepared to “creative” paths towards profitability — Palantir is planning to go public with a loss of $579 million in 2019 (The New York Times). But, most of all, we find it hard to predict how non-tech businesses will adapt to the post-pandemic world. The current bubble is not a bet on tech startups, it is a bet on the future of the world economy. There is no black box about the security itself — like in the dot-com bubble — but a radical uncertainty about the future that results in a hurry to sustain the only thing that seems to work like always: tech.

The result is that the bubble will burst only if the global economy will stop working as we expect it to work. The bubble might burst, but Big Tech giants will continue to have increasing control of traditional sectors like food production and delivery, mass media, public infrastructures, and military technologies. Some venture-backed startups might fail to deliver, but active secondary markets might still avoid losses for companies that struggle to generate profits, preventing the bubble from reaching the panic stage. To sum up: there might be a downstream speculation bubble driven by behavioral effects, but the economic foundations are incomparably more solid than those of the dot-com precedent.

The big picture

I want to leave you with a couple of reading recommendations. First, a new piece by Branko Milanovic on Foreign Affairs. This is a short article that explains how the world was made more equal by globalization, as measured by the Gini coefficient — but at the expense of Western middle classes. He identifies two fundamental tensions of globalization. One has to do with the evidence that “the income growth of the non-Western middle class far exceeds that of the Western middle class”. In other words, capitalism in developing economies still manages to give rise to a new middle class; on the opposite, in developed countries, the middle class is losing economic and political power. The second tension is “the growing gap between the elites and the middle classes in Western countries”, which increases infra-state inequalities by enriching the top 1% of the population.

This translates into a reduction in aggregate global inequality that is mainly driven by the incredible growth of developing countries, where a middle class can still emerge out of capitalism. After the slowing down of Chinese growth, this reduction of inequality will be driven by the economic development of India and Africa. In those countries, capitalism often corresponds to that “political” or “authoritarian” form that Milanovic identified in his Capitalism, Alone: The Future of the System That Rules the World. Here, he also introduced the future-oriented concept of “people’s capitalism”, which he sees as a potential balancing form of capitalism. This concept is partially adapted in the abovementioned article.

In the long term, the most optimistic scenario would see continued high growth rates in Asia and an acceleration of economic growth in Africa, coupled with a narrowing of income differences within rich and poor countries alike through more activist social policies (higher taxes on the rich, better public education, and greater equality of opportunity). Some economists, from Adam Smith onward, hoped that this rosy scenario of growing global equality would follow from the even spread of technological progress around the globe and the increasingly rational implementation of domestic policies.

This reduction in global inequality and the eradication of poverty requires a global effort to sustain economic growth. However, events like the trade war between the US and China make Milanovic skeptical about such an optimistic scenario.

The second recommendation is a new article by Abeba Birhane on the “algorithmic colonization of Africa” (Scripted). The basic theory is that the diffusion of Western technologies in Africa generates a new form of corporate-driven colonization, which not only alters local innovation processes but also maintains the existing power dynamics in the continent (see part of the abstract below). This is my piece of the week and I am curious to know your thoughts on the topic.

In the Global South, technology that is developed with Western perspectives, values, and interests is imported with little regulation or critical scrutiny. This work examines how Western tech monopolies, with their desire to dominate, control and influence social, political, and cultural discourse, share common characteristics with traditional colonialism. However, while traditional colonialism is driven by political and government forces, algorithmic colonialism is driven by corporate agendas. While the former used brute force domination, colonialism in the age of AI takes the form of ‘state-of-the-art algorithms’ and ‘AI driven solutions’ to social problems. Not only is Western-developed AI unfit for African problems, the West’s algorithmic invasion simultaneously impoverishes development of local products while also leaving the continent dependent on Western software and infrastructure.

Thanks for reading.

As always, I am waiting for your opinion on the topics covered in this issue. If you enjoyed reading it, please leave a like (heart button above) and share Reshaped with potentially interested people.

Have a nice weekend!

Federico