🌌 Reshaped #28

The power of symbols, Sovereign Wealth Funds, Apple's record market cap, unregulated stock speculation and much more

Welcome to a new issue of Reshaped, a newsletter on the social and economic factors that are driving the huge transformations of our time. Every Saturday, you will receive my best picks on global markets, Big Tech, finance, startups, government regulation, and economic policy.

For the second week in a row, I am not dedicating so much space to TikTok, which I would perceive as a piece of positive news. There is a common line throughout this issue and it has to do with symbols. Symbols have the power to activate bottom-up, participatory democratic processes; but they also function as the engine of political debate and public policy. Find out more in The big picture.

Please, take a moment to share this newsletter with your network!

New to Reshaped? Sign up here!

The State

State investments

This week, the world’s largest Sovereign Wealth Fund, the Norway Government Pension Fund, reported a $21 billion loss (CNBC). The value of the fund’s assets under management (AuM) is above $1 trillion and the loss is explained by the turbulent times of equity markets, which have been fluctuating heavily since the start of the pandemic. Almost 70% of the total AuM are invested in equities, which means that the fund is subject to the effect of fluctuations.

This is reflected in the nature of Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs). SWFs are investment funds owned by the state, which may decide to allocate its budget surplus to invest in traditional asset classes like equities and government bonds, or riskier alternatives like private equity — the SWF of Saudi Arabia notoriously invested in SoftBank’s Vision Fund, as already covered in this past issue. A recent paper by Salman Bahoo, Ilan Alon, and Andrea Paltrinieri provides a precise description of SWFs and their context.

The role of the state has been redesigned as an advanced, directorial, strategic actor that intercedes in investment in the form of the full ownership and control of state-owned institutional investors. This new influence of the state has ushered in a new era of state capitalism in which governments provide support to private firms. Under this “new state capitalism,” the nations that are enriched with a large amount of foreign financial reserves from national resources or trade surpluses have become symbolic institutional investors in the global economy through special-purpose investment vehicles called sovereign wealth funds (SWFs).

This description correctly distinguished between two kinds of SWFs. Non-commodity SWFs are financed by the accumulation of foreign currency over time; on the opposite, commodity SWFs are financed by the surplus deriving from the sale of commodities at a high price. The Norway Government Pension Fund, established in 1990, stems from the profits generated by oil trade. The uncertainty due to the pandemic hit oil stocks more than other sectors, driving the fund’s performance down.

The fund’s management is fearing a disconnection between the markets and the real economy, but some adjustments to the investment strategy are very likely to happen if the fund wants to be more independent from stock fluctuations (Financial Times). In part, this is already happening: according to the new report on SWFs by State Street Global Advisors, SWFs are adopting more mainstream investment strategies, leaving their contrarian investment behavior behind (see picture below).

Platform regulation

A few hours before the scheduled enforcement of the law AB5, which would have made mandatory for Uber and Lyft to treat their drivers as employees in the state of California, a delay was announced by authorities (BBC). Both companies were ready to shut down their activities in the state while considering a shift towards a franchising business model, which would have kept a sustainable cost structure (Bloomberg). Meanwhile, Doordash announced the launch of a new on-demand grocery delivery service in the US that will directly challenge Amazon and Walmart (TechCrunch).

However, the future of platform regulation also involves the relationship between citizens and the media. On CIGI, Ben Scott and Taylor Owen highlight three priorities “to realign the commercial incentives of big tech with the values of democracy and social welfare”. Their recipe consists of stricter regulation of algorithms and data collection, public oversight of information markets through specific institutions, and a new wave of investments in public media and digital literacy. The report is short, but it presents a linear flow from policy intervention (top-down regulation) to market creation (bottom-up facilitation). This is fundamental to keep the post-regulation market as fair as vibrant.

For more on platform regulation, a recent article on the Internet Policy Review can be considered as a primer for pre-crisis and in-crisis regulation. While the former must prevent platforms from becoming essential infrastructures for societies, the latter should carefully control their behavior so that they do not misuse their power in times of crisis.

The markets

Tech performances

While the global economy was suffering the consequences of a pandemic, Apple was rapidly increasing its market capitalization, which has now hit the $2 trillion record (The New York Times). The strong performance of tech stocks despite coronavirus only partially explains this achievement. Apple has taken a conservative road, with smaller bets on innovative products and a tendency to renovate its profit formula through business model additions like service bundles. Investors look at Apple as a company that has more potential to extract than before, due to the stabilization of iPhone sales and the recovery of the iPad product line. But, most of all, Apple benefits from periodical share buybacks that drive EPS up.

Meantime, SpaceX has closed a new $1.9 billion funding round with a valuation of $46 billion (MarketWatch). The company is planning new launches and is at the core of the race for the dominance of the new space economy. In parallel, Tesla is trading at more than $2,000 per share (Yahoo Finance). The growth in market capitalization is astonishing (+392% YTD) and reflects not only the achievements of the company (both operational and financial), but also the decision to split the stock to make it available also to average investors — and thus exploiting more broadly its huge brand equity.

Social media

A quick update on social media. Oracle joined the race with Microsoft and Twitter to acquire TikTok, thanks to its strict ties with the Trump administration (The Verge). At the same time, Facebook has enforced stricter rules regarding the QAnon conspiracy theory, removing dedicated groups and pages from its platform (CNet), while endorsing Epic Games in its clash against Apple and Google (Game Rant).

The speculators

Stock markets

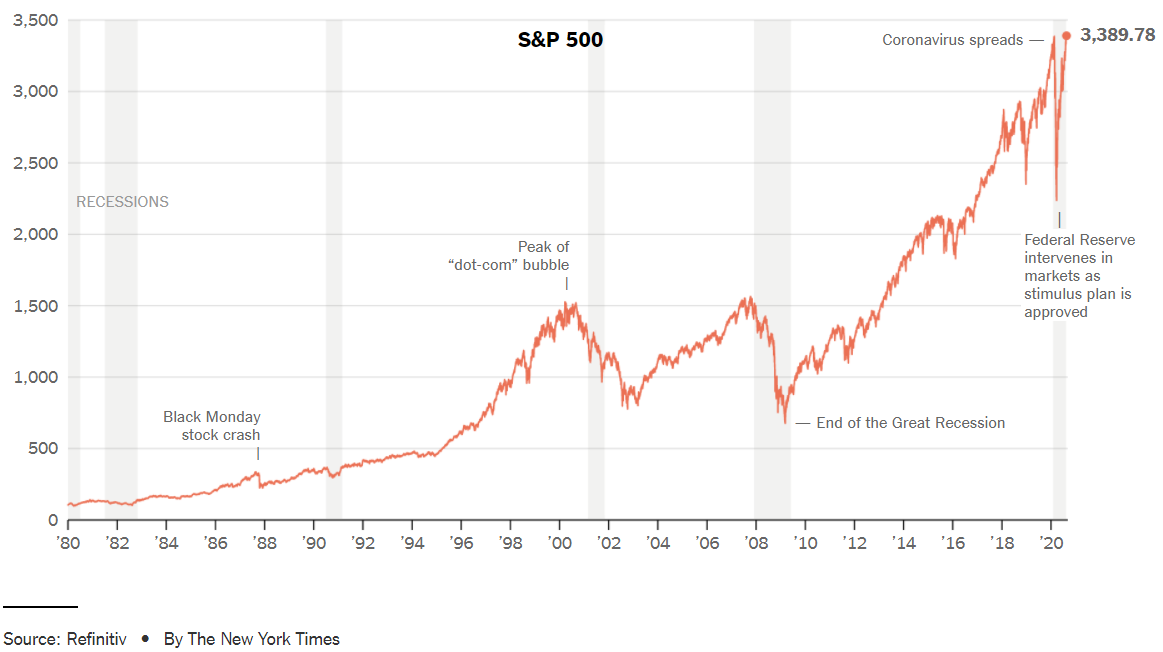

The S&P500 is back to the pre-pandemic level, ending the shortest bear market in history (The New York Times). After the initial shock, “the stock market began to recover and has done so steadily since, in a marked display of what analysts describe, by turns, as optimism, hubris or sheer speculative greed that is heavily reliant on federal spending, easy monetary policy and continued signs of progress in the hunt for virus vaccines”. Expectations surely play a pivotal role in the good performances of stock markets, but there is widespread concern about the sustainability of a financial system that is so much disconnected from the real economy.

Stock speculation

Robinhood continues its successful fundraising with a new $200 million round led by D1 Capital Partners and is not valued at $11.2 billion (Forbes). The company has raised some $1.7 billion during the last months and is successful at attracting new users to its platform. However, there is increasing concern regarding its business model, which relies on (young) unexperienced investors accessing stock markets to make risky bets (The Wall Street Journal). The 13 million users of Robinhood have the freedom to invest in stocks without entry barriers; however, this financial democracy can ruin thousands of naive investors who lack the necessary expertise to risk their money. Indeed, stocks markets’ safety nets do not even take into account this kind of micro-investor.

The SPAC boom (see this past issue for more on SPACs) is attracting new players from all around the globe (Financial Times). Alex Wilhelm even compared the SPAC wave to the ICO boom of 2017, when thousands of startups tried to find a new way to raise funds through initial coin offerings (TechCrunch). However, even if freedom from traditional IPO schemes is a common feature, the similarity is only partially correct: while ICOs kept the attention on the founder side, SPACs are focused on the sponsor. We went from the “freedom of the startup” to the “freedom of the well-connected SPAC proponent” — which is a more organized but less democratic way of accessing equity markets.

The big picture

On The New Left Review, Lola Seaton analyzes and comments Anatol Lieven’s recent book Climate Change and the Nation State. The Realist Case. The core thesis of the book is that it is fundamental to get a bipartisan commitment to fighting climate change; and, in order to do so, it is necessary to make conservatives involved in a Green New Deal project by focusing on the risk that climate change represents for the socio-economic stability of the nation-state. Focusing on some forms of “civic nationalism” can be a good way to unleash the symbolic power of climate change on both sides of the political spectrum; nonetheless, as Lola Seaton correctly points out, there is a risk of losing part of the reforming power of the Green New Deal.

The challenge, however, is to devise alternative senses of what ‘being realistic’ is by forging new expectations about what reality can and should be like […]. Moreover, given that much of the heating predicted by climate scientists in the coming decades is not preventable but guaranteed, domestic reform to mitigate climate change in the high-emitting countries of the global North […] needs to happen in combination with adaptation, including migration and development policies that do not trap impoverished populations in unliveable regions, whether this is sensu stricto in their ‘national’ interest or not.

This has to do with symbols and their power to activate the collective response. Those conservatives that complain against climate change policy — because it is seen as part of a liberal agenda that threatens the status quo — can still change their mind if they get convinced that climate change is the top reason for a radical change in the status quo. Politics is (also) about using the power of symbols to boost citizen participation. When symbols are anchored to evidence and when evidence is anchored to data, this mechanism functions as a necessary simplification of reality around the main drivers of ideology. Different symbols built on the same evidence can communicate with a broader population and make people involved without any form of manipulation. On the contrary, when symbols lose their link with evidence, the gap has consequences that range between optimistic illusion and unconscious militarization of minds.

Symbols also act as a system of self-defense. This happens whenever we describe ourselves as the victims of a particular social structure, without taking into consideration our role in its determination. A new article by Rachel Connolly on The Guardian explores how rich millennials make use of a narrative according to which they are the victims of the unequal economic system. They have the chance to enroll in the most prestigious universities and have access to their families’ current and future huge financial resources. However, they complain about rents (even if their parents are probably landlords) and difficult access to good working opportunities (even if they can afford those expensive MBAs that provide access to these jobs).

Of course, structural problems like rent, debt and finding meaningful work do affect many young people, particularly as some industries have contracted, making job opportunities in certain sectors scarce. But this reality has been warped to imply that such problems affect everyone approximately equally. The structural nature of these problems has come to mean almost nobody is responsible for causing them; instead they are the result of nebulous external forces, or an elite that is always conveniently defined as existing at the level of wealth above whoever is doing the defining. […] Elitism in the media industry has led to the strange phenomenon of mainly upper- and upper-middle-class millennials acting as dubious spokespeople for the impact of problems from which they are largely insulated.

Do not miss these other interesting pieces:

On OpenDemocracy, Maarten Hietland explains the relationship between tax heavens and the draining of resources from developing countries;

In their new paper, Mario Pianta, Matteo Lucchese, and Leopoldo Nascia analyze the opportunity for a new kind of European industrial policy, with a greater role of the state in the determination of the direction of investments;

On Aeon, Astrid Van Oyen reads the accumulation phenomenon with historical lenses to identify common patterns across centuries;

On Scientific American, Zeeya Merali reports about a new experiment that could have significant implications for quantum theory.

Thanks for reading.

As always, I am waiting for your opinion on the topics covered in this issue. If you enjoyed reading it, please leave a like (heart button above) and share Reshaped with potentially interested people.

Have a nice weekend!

Federico