🌌 Reshaped #55

The VC decision-making process, Central Banks into crypto and the Chinese path to net zero

Welcome to a new issue of Reshaped, a newsletter on the social and economic factors that are driving the huge transformations of our time.

🎙 You can still listen to The DART Bullseye on Spotify, Google Podcasts or Apple Podcasts. This week, Matthieu had an interesting chat with Manuel Opitz, Co-Founder and COO at Mercuris.

Please, take a moment to share this newsletter with your network!

New to Reshaped? Sign up here!

Before I dive into the topics of this issue, this is a short follow-up to Reshaped #54, in which I briefly wrote about the recent developments in carbon pricing mechanisms. A recent report by McKinsey explores the recent trend of private companies adopting internal carbon pricing. In short, they “are setting an internal charge on the amount of carbon dioxide emitted from assets and investment projects so they can see how, where, and when their emissions could affect their profit-and-loss (P&L) statements and investment choices”. The chart below summarizes the diffusion of this practice among companies in different sectors — see how polarized some industries (financial services, for instance) can be in front of this issue.

Some updates…

On Venture Capital

A new study published in the Harvard Business Review provides some invaluable insights into the decision-making process of VC funds. This is a list of some of my favourite findings:

Dealflow generation relies primarily (about 60%) on the VC network of investors, entrepreneurs (including portfolio companies) and professors. In deal sourcing processes, VCs have a very active role in initiating contacts with startups; only 10% of deals result from cold email pitches by startup teams. As a consequence, it is very hard “for entrepreneurs who are not connected to the right social and professional circles to get funding”.

For every startup that gets funded, VCs review 101 opportunities. 28 of them are invited to a meeting with the investment team, while only 10 are reviewed at a partner meeting. 4.8 will proceed to due diligence and 1.7 will “move on to the negotiation of a term sheet”. On average, each deal takes “83 days to close, and firms reported spending an average of 118 hours on due diligence during that period, making calls to an average of 10 references”.

Among the important factors driving investment choices, founders were the most frequently mentioned, followed by business model, market, industry and valuation. The scarce attention paid to the latter is part of a broader tendency to focus on non-financial metrics: “20% of all VCs and 31% of early-stage VCs reported that they do not forecast company financials at all when they make an investment”.

VCs have frequent interactions with portfolio companies and provide post-investment services such as strategic guidance (87%), connections to other investors (72%), connections to customers (69%), operational guidance (65%) and hiring support (58% for board members and 46% for employees).

On average, VC teams are composed of 14 employees and five senior investment professionals. The small size of these firms allows for faster decision-making at the expense of fewer checks and balances.

These results are even more relevant now that governments are pouring money into public VC funds. As reported by the Financial Times, the UK would be ready to invest £375 million ($519 million) in a follow-up of the Future Fund, the financial instrument that the government created to support startups during the first pandemic wave1. In the medium term, such an investment vehicle could drive part of the ownership of promising tech startups in the hands of the public sphere. But would that be good for the domestic innovation economy? In a recent paper, Gordon Murray explains that the role of the state in financing seed ventures is still fundamental despite the lack of a positive track record.

The emergence of the state as the single biggest investor in the early-stage VC market in several countries over the period since the collapse in the international market for new technology stocks in the year 2000, and more recently following the global financial crisis of 2007-9, indicates the centrality of the government’s role in the financing of both enterprise and innovation via the platform of start-ups and young companies. This focus is a substantial and continuing policy ambition for governments in both the developed and (increasingly) the developing world.

In addition, as reported by Marius Berger and Hanna Hottenrott in a recent paper, government VCs are more prone to do follow-up investments on top of previous public subsidies than other forms of VC funds. This is particularly relevant in the EU, where reliance on public grants is widely diffused among early-stage ventures.

On Cryptocurrencies

China is working on a state-backed digital currency. As reported by The New York Times, “the effort is one of several by central banks around the world to try new forms of digital money that can move faster and give even the most disadvantaged people access to online financial tools”. Most of all, this is an attempt to keep the crypto phenomenon — from Bitcoin to private stablecoins — under control by designing a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC).

In his recent article on Quillette, Alex Gladstein mentions CBDCs as one potential threat to the rise of Bitcoin.

Most central banks worldwide are experimenting with the idea of replacing banknotes with digital tokens that citizens could hold in mobile wallets. One argument that promoters of these systems make is that they could help check the thirst for Bitcoin. Ultimately, however, CBDCs like China’s DCEP can’t compete because their floating global price will be tied to the existing fiat currency, which will inevitably fall in relative purchasing power. Meanwhile, Bitcoin’s purchasing power continues to rise over time, and it offers a level of transactional freedom and privacy from the state that no CBDC could ever boast.

Apart from the extremely naive conclusion — based on overly simplified assumptions, especially regarding the use of Bitcoin for transactions — Gladstein is right to consider CBDCs as a potential long-term threat for other forms of cryptocurrencies. A recent report by PwC shows the diffusion of this phenomenon worldwide (see picture below).

In a recent speech, BEI General Manager Agustín Carstens provides some useful insights on the future of digital money that help understand why CBDCs could slow the growth of Bitcoin. First, he explains that “in the future, as Bitcoin approaches its maximum supply of 21 million coins, the ‘seigniorage’ to miners will decline”. This will change the balance of incentives in the system and “as a result, wait times will increase and the system will be increasingly vulnerable to the ‘majority attacks’ that are already plaguing smaller cryptocurrencies” (see chart below).

Second, he explains how cryptocurrencies — and in particular private stablecoins — could not be the solution for favouring transactions — hence, replacing fiat currencies.

I side here with Milton Friedman, who argued, “Something like a moderately stable monetary framework seems an essential prerequisite for the effective operation of a private market economy. It is dubious that the market can by itself provide such a framework. Hence, the function of providing one is an essential governmental function on a par with the provision of a stable legal framework.” This idea remains as relevant as ever in the digital age. So, clearly, if digital money is to exist, the central bank must play a pivotal role, guaranteeing the stability of value, ensuring the elasticity of the aggregate supply of such money, and overseeing the overall security of the system. Such a system must not fail and cannot tolerate any serious mistakes.

Without these “institutional” features, Bitcoin might end up being nothing more than a good speculative asset, with little chances of imposing itself as a pure transaction currency or store of value2.

On China

This week, the Chinese government announced a 6% economic growth target for 2021. The plan also includes a rise in military spending and lower dependence on foreign supplies of energy and technology (The New York Times). In 2020, due to the shock caused by the pandemic, China did not set any target, eventually closing the year with a 2.3% growth rate. However, much of the attention was paid to the environmental aspects of the new Five-Year Plan (FYP).

Months ago, China Dialogue anticipated the five key environmental goals to be revealed in the 14th FYP: a higher share of non-fossil fuels in the energy mix, a reduction of CO2 emissions per unit of GDP, a carbon cap for the power sector, a reduction of fine particle pollution in key cities and greater forest coverage. However, the announced FYP did not set an ambitious target for cutting emissions and makes it possible to double down on coal investments (The Guardian).

China will reduce its “emissions intensity” — the amount of CO2 produced per unit of GDP — by 18% over the period 2021 to 2025, but this target is in line with previous trends, and could lead to emissions continuing to increase by 1% a year or more. Non-fossil fuel energy is targeted to make up 20% of China’s energy mix, leaving plenty of room for further expansion of the country’s coal industry.

As reported by Bloomberg, this seems to reflect the need to maintain an agile agenda for post-pandemic recovery. Hence, a more detailed plan should be unveiled later this year.

The new five-year plan is the latest sign that China is employing a two-speed approach to tackling climate change. In the near term, it’s offering incremental improvements, such as reducing the intensity of emissions, while spending on research into technologies such as hydrogen and battery storage that it hopes will allow the nation later on to accelerate efforts to meet its 2060 goal. The slow start is a reflection that the government needs to restore steady growth to the world’s second-largest economy even as much of the planet remains in the grip of the pandemic, to help preserve social order and continue reducing poverty. Uncertainty over how quickly that can happen is reflected in the plan, which, for the first time in recent history, doesn’t include a five-year numerical target for GDP growth.

In particular, China did not reschedule its pledge to reach an emission peak in 2030. This could be a relevant problem for fighting climate change, as “China needs to peak its emissions as soon as possible, and certainly by 2025, to be in line with the Paris agreement” (Vox).

Other gems

AI investments. The newly released Stanford’s AI Index Report shows the evolution and the distribution of investments in AI over time. 2020 marked a record year, with $67.9 billion invested globally (+38.9% vs. 2019). The main driver of this growth was the surge in M&As due to corporate acquisitions of small businesses suffering from the effects of the pandemic.

Semiconductor competition. A new ITIF report explains how Chinese mercantilistic policies affect Moore’s Law in the chip industry3. According to the authors, Chinese subsidies to domestic producers are distorting the investment pattern of the sector, especially as it “reduces the pace of global semiconductor innovation by taking market share and revenue away from more-innovative non-Chinese firms”. This trade policy is consistent with the lack of a developed Chinese chip industry (see chart below).

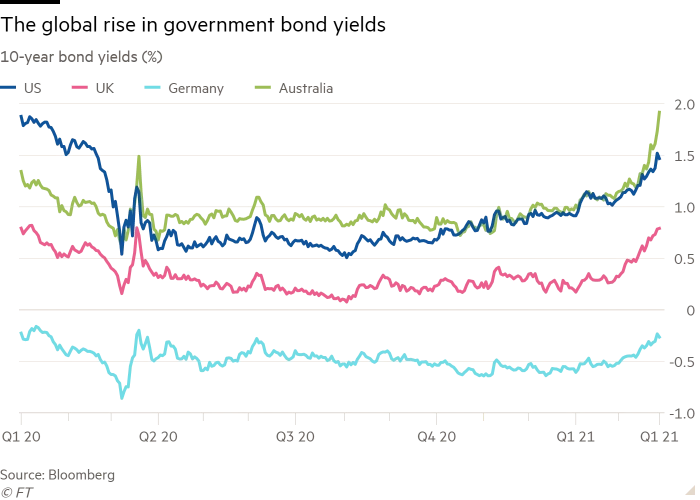

Bond vigilantes. The huge financial stimulus packages promoted by governments worldwide as a response to the pandemic are starting to generate domino effects on the bond market. As reported by the Financial Times, bond yields in 2021 are on the rise (see chart below) as a consequence of mass sell-offs. Is it a sign of the return of the bond vigilantes? For sure, it shows that inflation risk is perceived as a more relevant phenomenon when investors are used to historically low yields.

Commodity prices. A new report by John Kemp explains the cyclical behaviour of commodity prices. According to his analysis, cyclical price rises are due to high levels of demand occurring during intense industrialization phases (see chart below).

[…] commodity prices exhibit cyclical behaviour at all time scales, ranging from very short (minutes, hours and days) to very long (lasting months, seasons, years and even decades). In a typical cycle, rising prices encourage more selling and production, and less buying and consumption, creating conditions for a subsequent price fall, before the pattern repeats. In most cases, the cyclical behaviour of individual prices shows only limited synchronisation across commodity markets.

Thanks for reading.

If you enjoyed reading this issue, please leave a like (heart button above) and share Reshaped with potentially interested people.

As ever,

Federico

Recently, the UK government also announced the creation of a national research agency called ARIA (see Reshaped #54).

This point was recently addressed by Ray Dalio (see Reshaped #53).

The report is far too long to be adequately reported here. I strongly recommend you to take a look at it as it is plenty of extremely interesting data on the chip sector and its evolution.