🌌 Reshaped #42

Biotech investing after mRNA, Stripe on fire, misinformation policy, the "Money Trust", digital taxes and much more

Welcome to a new issue of Reshaped, a newsletter on the social and economic factors that are driving the huge transformations of our time. Every Saturday, you will receive my best picks on global markets, Big Tech, finance, startups, government regulation, and economic policy.

This week, I am briefly diving into the biotech sector before and after the COVID-19 pandemic; in particular, I tried to imagine how mRNA could change biotech investing by reducing overall risk for ventures.

Please, take a moment to share this newsletter with your network!

New to Reshaped? Sign up here!

Biotech investing after mRNA

After Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, the University of Oxford and AstraZeneca finally released the results of their clinical trials. The vaccine’s effectiveness is still unclear and ranges between 62% and 90% depending on the doses. In any case, it is far above the 50% threshold set by authorities. In the coming weeks, other pharmaceutical companies and universities will release the results of their experiments, bringing more clarity into the field — see this extraordinary tracker for more information on each vaccine research project.

The Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine is based on a viral vector. With respect to its mRNA-based alternatives, it is cheaper and easier to manage as it does not require freezing temperatures during transportation and storage. This is good news especially to make vaccines fairly accessible to developing countries and for reducing the overall risk of vaccination campaigns.

Apart from differentiation issues, however, most of the focus from both scientists and investors is related to mRNA vaccines, which have faster testing and manufacturing pipelines. The possibility to expand these advantages to other research domains like cancer therapies — BioNTech’s main focus — is extremely valuable for investors, which explains the skyrocketing valuations of some key biotech ventures. While I am writing, Moderna and BioNTech are trading at $127 and $110 respectively, up from about $20 one year ago.

Some argue that these valuations are only based on the press releases of biotech companies, which decide what to disclose and what to keep secret. This mechanism shifts the attention of investors from the final goal — solving the pandemic crisis, which requires a vaccine that both works and is manageable — to an intermediate step of the process — some good results to share. This is a legitimate claim, but it fails to acknowledge that viable investment alternatives for many equity investors would be much less relevant tech stocks. Not to mention the important role played by consistent communication about vaccines to build public trust.

Of course, the risk of a bubble remains. At the time it bursts, however, it will probably leave behind one or more effective vaccines and a new technological standard to advance medical research. After all, biotech is one of the most capital-consuming industries in the world. The mobilization of the vast amount of capital required to fight the pandemic paired with huge public spending naturally translates into stock hype and some form of speculation. At least, this time there is a positive correlation between the growth of market capitalization and the value of most biotech companies’ fundamentals — the latter being primarily driven by their technological progress.

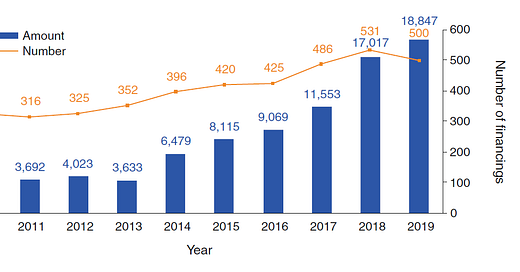

In addition, investors were pouring money into biotech ventures much before COVID-19. Globally, biotech VC deals have been growing in number and value almost constantly during the last decade (see picture below). Taken together, exits in the form of IPOs and M&As have followed a similar, positive trend.

This increasing level of investments ended up financing the same ventures that are now at the forefront of vaccine development. As explained by Julie Sunderland, co-founder and managing partner at Biomatics Capital, this is an example of a long-term investing attitude from both private and public investors. We can criticize the reward structure of VC-led innovation for being distorted (as I did here), but this is a clear example of an authentic risk-taking and ambitious investment strategy. In other words, this is more or less how a capitalist innovation economy should work.

Now, the shorter time required to experiment and produce drugs thanks to mRNA and other technological advancements could help to reduce the risk associated with biotech ventures — for an overview of how this risk is structured, see this past issue. Iterations would be easier, leaving more room for periodical reassessments. I see at least four big consequences for VCs:

Faster go-to-market could translate in each backed venture having a lower impact on the fund’s lifecycle, which could translate into more flexibility for GPs to manage their portfolios.

Ventures could explore new paths towards profitability (a privilege for bigger companies, see picture below) and become less dependent on exits.

Institutional investors might be more prone to financing biotech-specific funds, due to the reduced technological risk.

COVID-19 could disrupt the existing distribution networks — Amazon may be one factor driving this shift of power with its Pharmacy division — and open new opportunities for VCs interested in financing the commercialization phase.

The State

Tech policy

Donald Trump is planning to blacklist 89 Chinese aerospace companies with military ties, which would be prevented from having access to critical US technology (Reuters). This is just another chapter in the trade war between the two countries, which have restricted technological exports between each other several times during the last year. According to Salvatore Babones, Joe Biden should abandon any strategy to challenge China in its manufacturing leadership to focus entirely on maintaining the US technological edge (Foreign Policy).

Today it’s technology that ties the world together, not the container ship. To be effective in leading the United States in the 21st century, Biden will have to learn that dominance in technological networks is the key to success. There’s no harm in trying to reshore some manufacturing, as he talked about during the campaign, but it’s not going to shift the geoeconomic balance of power in the Indo-Pacific. If Biden really intends to get tough with China, he’ll have to double down on the U.S.-Chinese tech war that has seen Huawei crippled, Chinese semiconductor foundries put under severe pressure, and TikTok brought to the edge of divestment.

This is true but somehow fails to take into account the relevance of the debate around labor and manufacturing during the presidential campaign. Some sort of trade war with China for the recovery of lost manufacturing jobs would have probably been central in the campaign of any presidential candidate.

Digital taxes

France requested tech companies operating in the country to pay the 2020 installment of the domestic digital service tax, adopted last December (NBC). More specifically, this is a 3% tax on revenues generated in France “by companies with revenues of more than 25 million euros here and 750 million euros worldwide”. Meanwhile, the European Council adopted yesterday the conclusions on fair and effective taxation by the OECD, which should translate into a reform of the corporate tax system within the first half of 2021. This reform would include new international tax standards for crypto (Coin Telegraph).

In case of a new delay by international authorities, it is reasonable to expect that more countries will start to adopt their own digital taxes. Most tech companies already have some sort of “EU fines” cost in their financial statements; for them, digital taxes are probably going to represent nothing more than a new cost of doing business in the EU. However, this is a huge achievement for European democracies in their quest for fairness in digital markets. This can also be extended to developing countries, where, according to a recent report by ActionAid, the lack of an appropriate digital tax framework results in an outstanding $2.8 billion tax gap.

➡️ South Korean authorities fined Facebook $6.06 million “for providing users’ personal information to other operators without consent” (Reuters).

➡️ AI-driven pricing might favor collusion to the detriment of consumers (Science).

The markets

Stocks

For the first time, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (see picture below) closed at 30,000 “as financial markets around the world rally amid hopes for a coronavirus vaccine and smooth transition to a Joe Biden presidency” (The Guardian).

This is only apparently good news. As pointed out by Kevin Drum on Mother Jones, this is perfectly in line with the 5-year growth trend of the Dow Jones. In addition, it is quite difficult to draw any realistic picture of the global economy by looking at stocks during a pandemic.

It’s worth noting that there’s a genuine difficulty with economic data of all kinds right now: it’s almost all artificial because the state of the economy is dictated less by fundamentals and more by deliberate government lockdowns in response to the coronavirus. This means that the stock market, for example, doesn’t really tell us what investors think about the underlying strength of the economy. Rather, it tells us what investors think about how quickly the pandemic will be over and things will get back to normal. (They’re fairly optimistic about this.)

Social media

Fighting misinformation on social media is one of the greatest challenges for tech companies and public authorities. According to The New York Times, Facebook recently ran a series of experiments called “P(Bad for the World)” to train ML algorithms aimed at reducing the visibility of “bad” content. Up to now, however, AI seems to be more suitable for generating rather than removing misinformation on social media platforms. A recent report published on Brookings makes it clear that forms of AI-powered disinformation “can do their damage in hours or even minutes”, which translates into the need to react quickly to prevent them from spreading.

At the technology level, policies will need to be embedded into the algorithms in relation to questions such as: What confidence level that a rapid disinformation attack is occurring should trigger notification to human managers that an activity of concern has been identified? Over what time scales should the AI system make that evaluation, and should that time scale depend on the nature and/or extent of the disinformation?

Similarly, disinformation scholar Nina Jankowicz, author of How to Lose the Information War: Russia, Fake News, and the Future of Conflict, argues in a recent article on Foreign Affairs that the Biden administration should work ex-ante and focus on the improvement of the media and information space, with huge investments to boost digital literacy.

➡️ Salesforce is close to the acquisition of Slack, whose market capitalization rose from $17 to $23 billion after the news came out (The Wall Street Journal).

➡️ Apparently, OpenAI’s GPT-3 learned to code (The New York Times).

➡️ How did 16-year-old Charli D’Amelio become the most popular TikTok influencer with more than 100 million followers (The Atlantic)?

The speculators

Venture capital

Payment startup Stripe is close to a new funding round that would bring its valuation somewhere between $70 and $100 billion, up from the last private valuation of $36 billion back in April (Bloomberg). The new valuation would make Stripe the second most valuable private company in the world behind ByteDance. Founded in 2010 by the Irish brothers Patrick and John Collison with a mission to increase the GDP of the internet, Stripe has been growing constantly during the last five years, outperforming its main rival Square (see picture below). The surge in e-commerce caused by the pandemic had a positive effect on the financial performance of the company, which charges a hybrid fee (2.9% + $0.30 or €0.25) on each payment transaction processed.

Meanwhile, the VC industry continues to attract widespread criticism. In a new article on The New Yorker, Charles Duhigg explains how the VC industry has evolved from visionary to cynical and uninterested in the social outcomes of its investments. In particular, he stresses the unfair advantage that VC-backed companies have with respect to incumbents: despite huge losses and risky business models, the former can raise money and finance their market penetration to the detriment of the latter. Sometimes this positively disrupts industries, with trickle-down effects on the economy; too often, however, its impact is limited to the enormous rewards for founders and investors.

From the start, venture capitalists have presented their profession as an elevated calling. They weren’t mere speculators—they were midwives to innovation. The first V.C. firms were designed to make money by identifying and supporting the most brilliant startup ideas, providing the funds and the strategic advice that daring entrepreneurs needed in order to prosper. For decades, such boasts were merited. […] The V.C. industry has grown exponentially […], but it has also become increasingly avaricious and cynical. It is now dominated by a few dozen firms, which, collectively, control hundreds of billions of dollars.

This resonates with my idea that large, generalist VCs have little to do with the advancement of technological innovation, especially when they leave too much power to inexperienced founders and do not provide sector-specific support.

➡️ The insurtech startup Hippo raised a new round worth $350 million to expand its business in the US (Crunchbase News).

Asset management

The asset management industry is notoriously becoming more and more concentrated at a global level. The “Big Three” asset management companies (BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street) control $15 trillion in assets as a consequence of the increased relevance of passive funds during the last couple of decades (see picture below). This is why, in a new report, Graham Steele from the American Economic Liberties Project argues that we should regulate this money trust, “a system of financial architecture dominated by a few large banks, private equity firms, and hedge funds”. The report is a very recommended long read, with plenty of details and historical references.

According to Steele, policymakers should face this challenge with a holistic approach that reflects the multifaceted market dominance of these companies — which is very similar to what is already happening in tech antitrust.

Rather than being isolated business lines, each function of the Big Three asset managers serves the ultimate goal of increasing concentration, power, and, ultimately, profit. Public authorities often approach their responsibilities in silos, caring narrowly about their specific mandates of financial stability, competition, consumer and investor protection, and so on, but the risks posed by the modern asset management industry require an approach that combines structural reforms and better regulation.

The big picture

On Aeon, Michael Strevens wrote a beautiful and provocative essay on the importance of the irrational side of science, which is often left behind in the scientific debate.

[…] the principle that only empirical evidence carries weight in scientific argument is widely enforced across the scientific disciplines by scholarly journals, the principal organs of scientific communication. Indeed, it is widely agreed, both in thought and in practice, that science’s exclusive focus on empirical evidence is its greatest strength. Yet there is more than a whiff of dogmatism about this exclusivity. […] What about other considerations widely considered relevant to assessing scientific hypotheses: theoretical elegance, unity, or even philosophical coherence? Except insofar as such qualities make themselves useful in the prediction and explanation of observable phenomena, they are ruled out of scientific debate, declared unpublishable. It is that unpublishability, that censorship, that makes scientific argument unreasonably narrow.

I am leaving you with some other reading recommendations:

Is space mining a viable and sustainable solution to circumvent the depletion of natural resources on Earth (Discover)?

The debate on the cancellation of student debt is back in the US and some see it as the only way to go (Current Affairs).

With increasing investments in renewables, the Italian energy giant Enel is at the forefront of the European green transition (The Economist).

Companies use tactical spinoffs to avoid liabilities related to environmental externalities (ProMarket).

Thanks for reading.

As always, I am waiting for your opinion on the topics covered in this issue. If you enjoyed reading it, please leave a like (heart button above) and share Reshaped with potentially interested people.

Have a nice weekend!

Federico