🌌 Reshaped #12

Special issue: the future of venture capital

Welcome to a new issue of Reshaped, a newsletter for those who do not want to miss a thing about the huge transformations of our time.

As anticipated, this issue is dedicated primarily to the analysis of future scenarios for the venture capital industry. The pressure on the innovation ecosystem to provide valuable responses to the big challenges of our time necessarily translates into the need for a new role of VCs as true risk-takers. I am curious to know your opinion on that.

Do not forget to share Reshaped with potentially interested people in your network!

New to Reshaped? Sign up here!

News

Business and Finance

🚗 Uber is considering laying off 20% of its workforce (more than 5,000 people) due to reduced business, including technical staff — which might have caused CTO Thuan Pham to resign (The Information).

🚬 Juul Labs is going to cut 25% to 40% of its total workforce, equal to about 3,000 people, due to scrutiny from regulators and shrinking sales (Bloomberg). According to CB Insights, Juul Labs was the most financed startup in Silicon Valley in the first quarter of 2020, with a $700 million deal from undisclosed investors.

🗽 US Democratic congresswomen Elizabeth Warren and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez endorsed David Cicilline’s proposal to stop M&A activities during the pandemic, except for emergency deals to save companies in financial troubles (The New York Times).

💻 Despite the forecasted reduction in advertising expenditures, Facebook and Google showed resilience in their advertising businesses thanks to the “direct response” campaigns, which allowed the two companies to report growing revenues (Financial Times).

Science and Technology

🤖 Scientists have made progress in the empowerment of artificial intelligence with common sense, which has always been a weak point of AI systems (Quanta Magazine).

💉 More than 90 COVID-19 vaccines are under development, and now scientists have to set the stage for understanding which of them actually work, which will require a huge coordination effort between countries (Nature).

🚙 New research shows the consequences of gas and diesel vehicle emissions on climate change and human health, with more than 200,000 premature deaths per year (Eos).

🔮 The future of venture capital

Venture capital (VC) is experiencing a multi-faceted conundrum. On one hand, it is one of the most hyped sectors in the world, capable of attracting top talents and impacting the most important business trends of our time. On the other, it is facing criticism for being unable to foster innovations with the potential to radically improve human living conditions and solve pressing challenges such as climate change — especially because of short-termism and blitzscaling imperatives, which negatively influence capital-intensive and science-based ventures. In this short essay, I will try to explain why VC alone falls short of solutions for the huge challenges of our time — in particular as a consequence of the shock caused by COVID-19 — and how it could be reshaped by new political and financial trends in the years to come.

There are at least four books I would recommend you for a deeper analysis of this topic:

Tom Nicholas, VC: An American History (Harvard University Press, 2019);

Mariana Mazzucato, The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths (Penguin, 2018);

William H. Janeway, Doing Capitalism in the Innovation Economy (Cambridge University Press, 2018);

Carlota Perez, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2003).

I consider the latter one of the best books on the intersection between technological and financial dynamics, and I strongly recommend it to readers interested in understanding how technological revolutions generate (and are impacted by) financial cycles.

First of all, it is important to remember that venture capital is an American phenomenon. Heavily imitated abroad, yet purely American. As clearly explained by Tom Nicholas, whose book is a rare example of historical analysis applied to business practices, the venture capital industry was born as a result of government efforts to foster rapid growth in the middle of the XX century. (The analysis of the author starts from XIX century whaling, and the comparison between the two risky business is extremely fascinating.) Starting from the 1970s, deregulation in the form of capital gains tax cuts and fewer restrictions for investment banking created a link between the rising PE industry, the technology sector (including the many publicly funded projects in the US), and ambitious VCs. The rise of the latter was primarily a consequence of the speculation of these decades.

In the abovementioned book, William H. Janeway provides a beautiful description of the original spirit of VCs.

The Innovation Economy by definition is saturated in unquantifiable uncertainty. The emergence of a venture capital industry focused on funding start-up companies was supported by recognition of the need to offer abnormal rewards for success. The goal was to construct an economic asset in the hope of eventually monetizing it in the public equity markets. The possible returns had to be abnormally high, given how very rarely it was reasonable to expect such success to be realized. By 1980 or so we were calling equity-based compensation “Silicon Valley socialism”: every employee in a start-up, from the CEO through the technical architects and programmers to the receptionist was entitled to participate.

This description illustrates the rationale behind VCs: if a new venture is too risky for borrowing from banks, another type of equity investor is needed. “Abnormal rewards” are the balancing factor in this economic system — and it explains why Janeway, contrarily to Mazzucato, believes that financial speculation is key to technological innovation. However, recent trends in the sector show how VCs have gradually shifted from high-tech to consumer investments. As a consequence, their impact on economic development is extremely reduced. We may say that the impact of VCs in the last decade is limited to market dynamics that have nothing to do with progress or the advancement of society. Without them, we would love different brands and use slightly different products and services, but the technological level would be unchanged.

As perfectly argued by Mariana Mazzucato in the abovementioned book, it is difficult to identify a relevant role for VCs in the development of our economies.

Impatient capital can destroy firms promising to deliver government-financed technology to the masses, but critics often focus on the government as the source of failure rather than examining the behaviour of the smart, profit-hungry business community in producing that failure by jumping ship, restricting their total commitments, or demanding financial returns over all other considerations. If VCs aren’t interested in capital-intensive industries, or in building factories, what exactly are they offering in terms of economic development? Their role should be seen for what it is: limited. More importantly, the difficulties faced by the growing clean technology industry should highlight the need for better policy support – not less, given that existing financing models favour investors and not the public interest.

This reflects a drastic reduction in the risk level of venture capital investments. Indeed, ICT companies merely fight for little slices of the market with no technological ambition. Things could be different with the rise of AI, but commercialization is still at the beginning, while some argue that a new AI winter is coming — meaning that, similarly to what happened in the 1980s, the AI revolution will have to wait for better times. Nowadays, typical VC investments pursue high growth in the short term with little technological complexity and low capital intensity. However, awards are still too big to reflect this downwards trend in risk-taking, even if the public market (NASDAQ included) is more skeptical and deals are decreasing.

As explained by Mariana Mazzucato, even in the case of biotech, a typical investment area for VCs, the final objective consists in exploiting public research, patenting a new solution, and exiting in a secondary market with an acquisition aimed at outsourcing R&D activities — a negative consequence of the misunderstanding of the open innovation concept. This has terrible effects on the commercialization of science-based solutions, which would require more time and dedication. Moreover, it shows that in the scientific domain VCs are not doing their job properly, with negative consequences diffused to other sectors and the whole economy. This applies also to the green revolution, a domain heavily affected by Evgeny Morovoz’s concept of “solutionism”, as the recent declarations on the European Green Deal demonstrate (see this past issue for more on that).

Due to the strict tie between innovation and the advancement of our societies, the venture capital industry should be less focused on profits and more directed towards technological development. What the investment portfolios and the communication strategies of the major VCs show, however, is that in the last decade the venture capital sector has mainly concentrated its efforts in playing a game. The game is open for self-styled business pioneers, technology geeks, nerds of various types, and — a more recent trend — brilliant futurists who know how the future will look like in an indefinite time horizon. VC-dense (yet often VC support-lacking) startup ecosystems all over the world were born as local communities of those who desperately wanted to be part of this game. In their perspectives, getting funded by a VC is by itself a proof of value that translates into a status symbol inside the community.

In addition, the blitzscaling imperative (grow fast or go home) can hardly coexist with scientific progress. The big pressure put on founders — who nowadays are a commodity to exploit as far as possible — to grow their business at the pace of the proper return on investment instead of the proper business development has enormous consequences on companies and markets. The impact on companies goes from inadequate business model validation to bad organizational models, as seen in the Uber case. Markets, on the other hand, have no time to settle in with the dramatic rise of new “tech” giants, powered with absurd valuations and no profitability at all. Some think that alternatives to unicorns will be successful after the coronavirus, when blitzscaling will be no more imperative. However, there is little evidence of a change of attitude in that sense.

Let me stress a point: playing games is absolutely legitimate. Nevertheless, VCs have branded themselves as the competency-driven crafters of a better world. The innovation deadlock we are experiencing, curiously, tells another story. VCs have focused on the short-term because their business model forces them to do so. The end of the game has to coincide with a relevant reward for both investors and VC managers. This is also legitimate. What is not legitimate is making people believe that the game is providing rewards for society or advancing the technological and scientific level of our industries.

Some years ago, Steve Blank, famous for having brought to success the “customer development” process that subsequently morphed into the lean startup movement, criticized VCs for the excess of speculation of the industry, which he defined a giant liquidity Ponzi scheme. This means that the participants of the game, far from being active participants in the race for a better world — and, in turn, for a privileged position in it — are puppets whose primary function in the system consists in spreading and nurturing the hype in the Venture World. When the Ponzi scheme reaches the next and final stage of the speculation curve, the Minsky moment, the collapse rewards only a few players of the game to the detriment of all the others and those who will want to play in the future.

The current shock, paired with the increasing saturation of the market for digital products, might reveal that we are already in a Minsky moment — that is, the startup ecosystem that VCs have contributed to nurturing for decades might face a huge decline in valuations. Investors usually say that when bubbles generate crashes, the technology advancements remain, as well as the benefits for society as a whole. This obscures the hidden consequences of those crashes on virtuous investors that entered later in the industry and concentrated mainly on the long-term — which is what many small, sector-specific VCs are doing right now. They also forget that thousands of people — young entrepreneurs, highly specialized professionals, and students —, who were told that the crashed bubble was the catalyst of a better world, will feel betrayed, as happened after the Dot-com Bubble.

Venture capital investors are aware of the risks. In a recent post that went viral on Twitter, Founders Fund’s Principal John Luttig argues that the era of exponential growth in many technological categories is ended, with decreasing incremental expenditures in digital assets. Basically, people are plenty of digital services and there is little room for new ones — which generates the saturation of the digital market. Consequently, tech companies will shift from pull to push strategies, which will reward incumbents (with more marketing firepower) to the detriment of newcomers. This will generate four main effects:

More zero-sum games between tech companies, with more competition for market dominance and an increase in M&A activities;

The gradual transition from R&D to SG&A expenses to cover the increase in marketing costs, which he calls the “operationalization of Silicon Valley”;

VCs will start focusing more on vision than numbers;

Founders will change to reflect the new need for operation champions.

I do not agree with all the findings of the author — but most things I disagree on seem to spur from our different professional backgrounds, which have no relevance here. However, the idea that the space to compete will be even narrower in the future is an evident trend. Also, the operationalization of Silicon Valley, which he links to the involvement of more traditional financial actors providing debt instruments to startups, finally capable of forecasting growth with more accurate metrics, is a brilliant intuition. On the other hand, zero-sum games are already the standard in the industry (see what market dynamics have been unleashed by Zoom’s recent success), but VCs have no interest in disclosing that in their narratives.

In any case, the operationalization of Silicon Valley seems consistent with the greater focus of VCs into a startup’s vision. With debt instruments becoming available to startups than once could only rely on equity investments, VCs will have to turn their attention to those startups that, because of their sector or business model, will not have access to debt instruments. However, this would mean either relying on low-quality or high-risk ventures. The former can be excluded for sure: VCs will never accept such a downgrade in the financial landscape. On the opposite, vision-driven, high-risk ventures could finally enter the radars of VCs, which would somewhat recover some of their original (elitist) social responsibility.

(If you noticed a contradiction between the dominant narrative of VCs as vision-oriented endeavors and the future trend towards a more vision-oriented kind of VCs, you are not alone, but this is Venture World and we are probably too fussy.)

However, this could happen only if VCs will reform the current reward system to promote long-term investing. This goes far beyond their business model to encompass structural dimensions such as VC lifetime — ten years could be a very short timespan for long-term ambitions. Another important factor would be the creation of a new form of engagement with research institutes and governments. Publicly recognizing the strict tie between the origin of VCs and governments, and between the latter and innovation success cases will be a first, crucial step towards a functioning Schumpeterian innovation system. Nonetheless, it seems this is not happening during the pandemic.

Recently, VCs in Europe and the US have intensely lobbied for accessing government recovery funds, despite having reserves that could easily support backed ventures for at least one year. I have written about the insane idea of supporting startups with public funds in past issues. However, some see a possibility for governments to engage more proactively in the commercialization phase of the innovation process by turning loans into equity purchases. I tend to be skeptical, as the most efficient way for governments to engage in this process is by providing a market for new ventures — that is, buying new products and services to generate revenues for innovative companies, as happened in the US with Apple. Moreover, buying equity during a crisis that will potentially reshape markets and supply chains is extremely risky even for the most courageous governments — unless the target startup is technologically or scientifically advanced enough to justify state ownership.

Even without the government as an active player in the commercialization phase, VCs will have to face a trend that is already reshaping the startup communication — and that, in the next months, is likely to change their product and marketing strategy as well. The fight for relevance in the low-touch economy, as many analysts have pointed out, will reward startups that provide essential services or those that have the potential to generate broad scientific and technological advancements. This could generate a stronger focus on an investor’s expertise in a specific domain, instead of financial availability or network positioning. Consequently, this could benefit small VCs with sector-specific portfolios and capabilities, which could raise new funds and attract new ventures.

To sum up, the mix of technological cycle effects and exogenous consequences of COVID-19 will decide whether VCs will continue to play a relevant role in our economic system or not. At the moment, their contribution to the development of the latter is far from what the dominant narratives are prone to tell. However, the restructuring of our innovation ecosystems and processes to truly address the big challenges of our time (climate change above all) will require the active participation of governments, banks, and expert entrepreneurs willing to provide their expertise in the growth of new, socially meaningful ventures. Some VCs correspond to that definition, but the vast majority do not, focusing only on short-term growth and easy returns. COVID-19 might pressure VCs to rediscover their risk-loving soul or, on the contrary, reduce even more the structural differences with private equity funds.

Whatever the future of VCs, it will be heavily influenced by the role played by the other actors of the economic system in this critical period. Governments, especially, have an unprecedented chance to play an explicit leading role in innovation, paving the way for new economic structures where actors that are rewarded as high-risk investors actually take those risks.

Alternative perspectives

🛑 In an article on The Guardian, George Monbiot makes the case for stopping any financial support to the airline, oil, and car industries to avoid a return to the status quo, as happened after the 2008 crisis. According to the author, climate change should be addressed with drastic measures that go far beyond stimulus packages and include radical industrial policy.

Governments should provide financial support to company workers while refashioning the economy to provide new jobs in different sectors. They should prop up only those sectors that will help secure the survival of humanity and the rest of the living world. They should either buy up the dirty industries and turn them towards clean technologies, or do what they often call for but never really want: let the market decide. In other words, allow these companies to fail. […] The “free market” has always been a product of government policy. If antitrust laws are weak, a few behemoths survive while everyone else goes down. If dirty industries are tightly regulated, clean ones flourish. If not, the corner-cutters win. But the dependency of enterprises on public policy has seldom been greater in capitalist nations than it is today. Many major industries are now entirely beholden to the state for their survival.

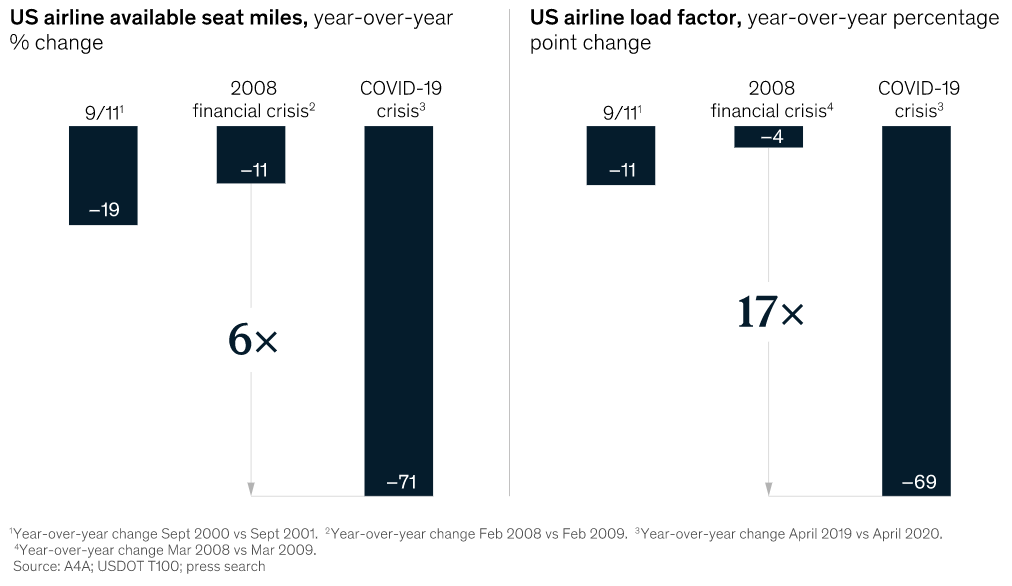

With no doubt, bailouts to airlines are a big risk for governments, due to the unexplorable future of the industry — which, in turn, will affect the oil sector. McKinsey provides an estimate of the impact (see charts below), with a worst-case scenario in which

demand drops by about 60 to 70 percent in 2020 and does not recover to pre-crisis levels until 2023 or even later.

🚨 On Brookings, Chris Meserole analyzes how COVID-19 has already impacted on the public conversation on the relationship between power and technology, with a reduced techlash sentiment and a diffused resignation to Big Tech dominance. In the near future, antitrust and privacy protection will have to adapt and get back on track.

Faced with a global pandemic, the techlash has been put on hold. Yet the issues that drove it haven’t gone away. A decade in the making, the backlash against the technology industry stemmed not from a single overriding concern but several overlapping ones—particularly anti-trust challenges, privacy violations, and online harms. The extent to which the pandemic will reset the broader tech policy conversation depends on how it intersects with those issues. In each case, Big Tech is likely to become even bigger and more powerful than before. […] The tech industry is likely to end the pandemic even more entrenched and powerful than when the crisis started. Prior concerns about the industry’s market power, privacy practices, and content moderation policies—all of which posed a major challenge just months ago—no longer enjoy the same political salience.

Other readings

📉 The private equity industry is facing a difficult moment, which could have long-lasting impacts on the financial sector and put an end to a decade of good deals, boosted by lax regulation and low interest rates (Bloomberg).

🏦 Because of its recovery plans, the Federal Reserve is reshaping the traditional role of a Central Bank, which could have permanent effects after the pandemic (The Wall Street Journal).

🔧 On The New York Review of Books, Maeve Higgins analyzes how, in the US, essential workers are not treated as such, with little intervention to mitigate systemic inequality.

🥤 Nobel laureate Paul Romer compares virus tests with sodas to provide an easy explanation of the regulatory and economic dynamics behind COVID-19 testing.

💣 Former Google CEO Eric Schmidt is striving to become the official liaison between tech giants and the military sector in the US — even if its strong, persisting interests in Google would make him a suspicious intermediary (The New York Times).

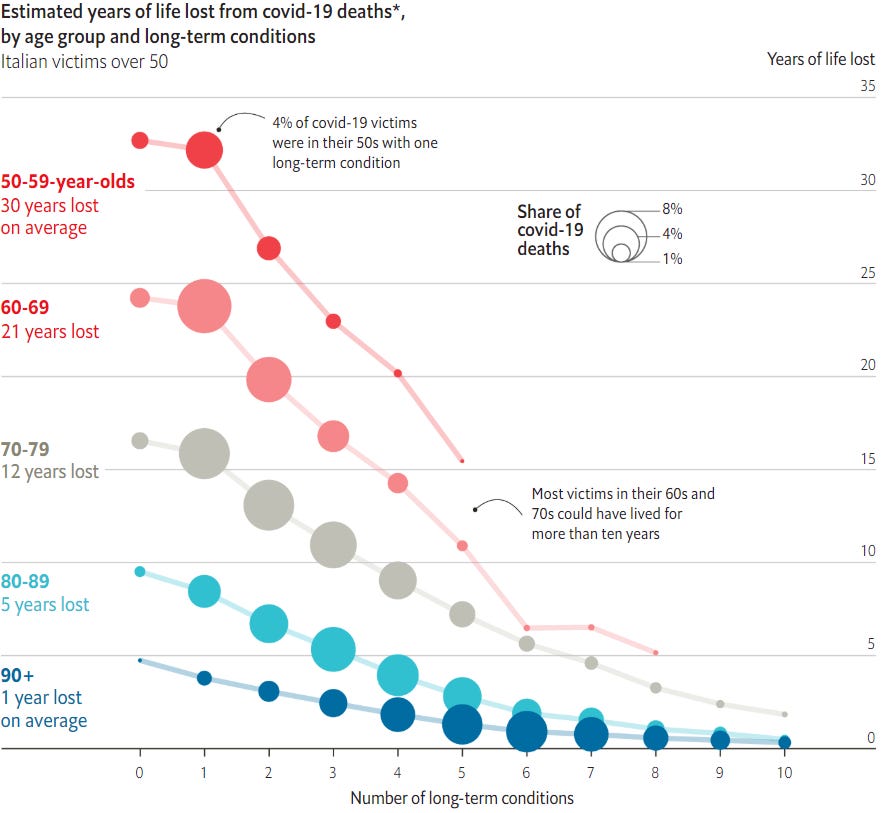

⚰️ The Economist analyzed the years of life lost from Italian COVID-19 deaths, which shows that the coronavirus is not only a problem for the elderly.

Thanks for reading.

Please give me any feedback about this issue. If you enjoyed reading it, like and share Reshaped with potentially interested people.

Have a good weekend!

Federico