🌌 Reshaped #7

Special issue: coronavirus and the neoliberal paradigm

Welcome to a new issue of Reshaped, a newsletter for those who do not want to miss a thing about the huge transformations of our time.

This issue is dedicated to deepening the relationship between neoliberal capitalism and the current coronavirus crisis. Is there a chance to rethink our economic system? Answer to this email and join the debate.

New to Reshaped? Sign up here!

News

Business and Finance

💸 COVID-19 is having a huge impact on startup funding, as seed investments have dropped by about 22% globally in the first quarter compared to previous forecasts. This will impact how big companies will acquire talents and promising technologies in the months to come (The Wall Street Journal).

🛕 Facebook could be interested in acquiring a 10% stake in the Indian telecommunication company Reliance Jo, which has a $60 billion valuation, to improve its market position in the country (Financial Times).

👀 Microsoft will stop investing in external facial recognition ventures due to polemics related to its funding of the Israeli startup AnyVision, accused of having run surveillance programs (The Verge).

📉 The global pandemic is causing trouble in the hedge fund industry, which is registering bad performances worldwide (Financial Times).

Science and Technology

💉 In order to speed up research, scientists could test vaccines directly on humans, but this entails ethical issues difficult to solve (Nature).

🐔 The correlation between the spread of COVID-19 and the consumption of meat is not limited to Chinese markets selling exotic food: intensive animal farming has a direct impact on the diffusion of diseases (Scientific American).

🚀 The US Space Force, established by Donald Trump in December 2019, has launched its firsts satellite despite some technical problems and a global pandemic (Space).

🏺 The use of ceramic in the lithium extraction process could strongly reduce costs, but it is hard to scale (Chemistry World). Making the extraction process more sustainable is key to a faster transition to renewable sources of energy.

📱 Social distancing caused an increase in the use of the internet, but providers are confident they can handle the load (Popular Science).

🩹 Curing the system

When, during the 70s, neoliberalism became the dominant school of thought in economics after more than a decade of careful preparation and continuous attacks on the Keynesian economic policy (see the dedicated chapter in Matt Stoller’s Goliath for a brief explanation of this process in the US), the world seemed to enter a new era of prosperity characterized by three main factors: unregulated globalization and free trade, privatization and deregulation of key public strongholds, and broad laissez-faire that ultimately translated into the application of Robert Nozick’s night-watchman state. Through the Washington Consensus and targeted foreign policy choices, neoliberal principles spread across the globe to destroy barriers to trade and impose austerity to the detriment of social conditions and historical contingencies.

The result of the wide application of neoliberalism is very different from what its creators had promised more than forty years ago. Trickle-down economics was a bet that the reduction of taxes on businesses and the wealthy classes would generate positive effects on society as a whole in the long term. The result, though, was a tremendous spike in inequality both in developed and developing countries, with the return to some forms of pre-industrial, patrimonial societal structures. This was already evident during the Reagan and Thatcher age, but Francis Fukuyama’s end of history and the preposterous logics that only more liberalism can save the world from the negative effects caused by liberalism itself made the system buy almost twenty years — thus delaying structural reforms that could have transformed capitalism before the 2008 crush.

However, the response to the financial crisis that hit the world twelve years ago was again in line with the neoliberal playbook. The rewards of thirty years of financial speculation were enjoyed by a few wealthy speculators, but their tragic consequences were absorbed by global societies and the public sector through bailouts to the financial sector itself (probably the most absurd political choice of the whole neoliberal era) and years of austerity that further weakened governments worldwide. Financial speculation, however, was a collateral consequence of neoliberalism: some could still argue that there was a better way to do capitalism under neoliberal thinking. That is why it survived during the following decade until the COVID-19 turmoil.

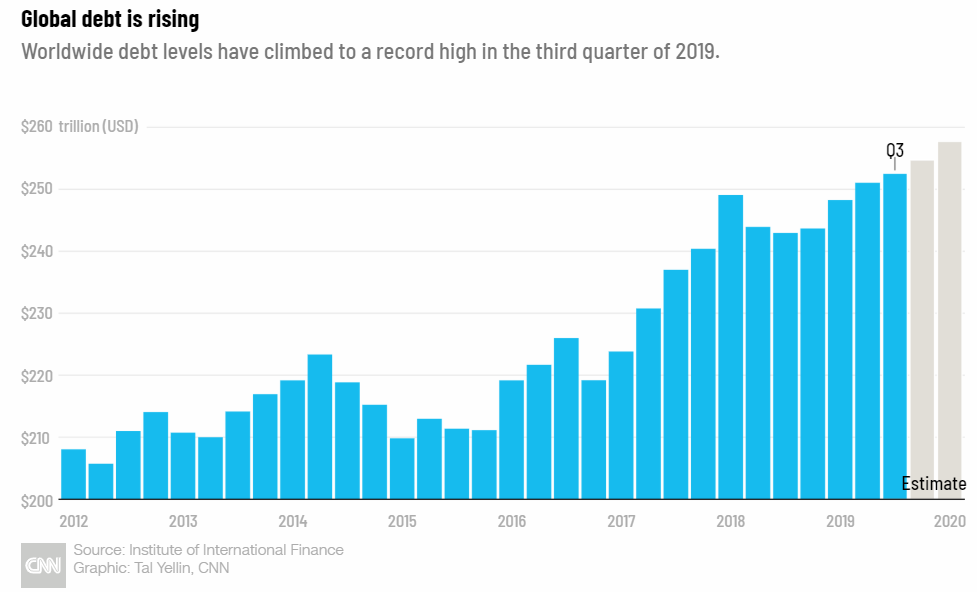

However, the new crisis is different, being rooted in neoliberal capitalism’s structure much more than the previous one. Indeed, neoliberalism mainly failed in investing in society at least part of the enormous profits generated by free trade and deregulation, with weakened national governments forced to fill the gap. Overaccumulation’s stagnant capital was used to finance even more speculation instead of strategic investments or industrial production. Even more, debt (both public and private) continued to increase to levels unseen before (see chart below) and is now more than three times the global GDP. This debt, however, was not functional to growth, as the low growth rates confirm, and thus ended up financing the speculation scheme that brought us to disaster in 2008.

Now that the coronavirus epidemic has unveiled the inner contradictions of neoliberalism, it is time to radically rethink our economic systems. But how exactly did neoliberalism influence the spread of the virus across the globe and the economic crisis that will follow?

First, by allowing free markets to destroy the essential connections of the agrifood sector with society. This holds true not only in the intensive animal farming industry, where thousands of animals live together in terrible hygienic conditions — thus improving chances of contamination and virus mutation — but also in the food market deregulation occurred worldwide. Allowing the creation of strong agrifood monopolies, China forced SMEs to sell alternative products in niche markets: exotic meat such as bats, killed in front of the customer to increase the price, was a fundamental factor in the transmission of the disease from animals to humans. Papers show how academics have been warning against these practices for the last twenty years, without being heard by national authorities.

Second, by forcing people to move to metropolitan areas, where financial-driven economic activities are located. This had two major consequences. On one hand, urban masses living in little spaces — and, in some areas of the world, in bad hygienic conditions — are more difficult to isolate to avoid the spread of epidemics. On the other hand, non-metropolitan areas are less reactive to pandemics because of the reduced healthcare capacity, as demonstrated by the reduction of hospitals in the European suburbs during the last decade in favor of metropolitan centers.

Third, by weakening healthcare systems through a dangerous mix of austerity and privatization that drastically reduced prevention and reaction capabilities. In the last issue, I analyzed how important it is to slow down the spread of the virus to build healthcare capacity and increase ICUs, especially because there is an opposite force that constantly reduces this capacity every day — in the forms of deteriorated assets and healthcare staff getting sick. The debate on public healthcare for all in the US over the last months, and in particular during the Democratic primaries, seems now illogical, with only one road left to take. At the same time, the hesitation of Western governments to take drastic measures against the pandemic shows how the public sector is plenty of charlatans, subjugated to neoliberal forces that ultimately legitimate their political power, that try to defend capitalist structures until the end.

Finally, by deregulating international markets without any measure to protect vital supply chains. As a result, lockdowns and the interruption of supplies have shocked the economy, bringing to the fore the weakness of our systems based on cost-effective outsourcing and just-in-time production resulting in low inventories. Not only the neoliberal paradigm was unable to create the value it promised and that would (to some extent) justify its own existence, but it also weakened the global economy. The situation is unrecoverable through monetary policy, as the recent Fed moves demonstrate. After all, in past crises, lowering interest rates and injecting liquidity meant even more chances to do speculation and subsidize corporations, with no investment in welfare. A direct intervention of the state in restoring adequate production and demand levels through helicopter measures is showing again that neoliberal capitalism is unable to heal itself, as it requires public intervention — thus breaking the laissez-faire dogma.

There is a chance that we rethink our economic system to avoid the resurrection of the neoliberal paradigm at the end of the emergency. Some of the bailout principles outlined in the last issue are a good starting point to prevent public money from being used to save powerful corporations that have bought back their stocks during the last decade instead of investing to produce value. For sure, there is no playbook to apply. However, the most urgent measure is to avoid mass layoffs, so that corporations have less space to impose even more austerity conditions on workers, as happened after 2008 with a surge of precariousness. Unfortunately, neoliberal capitalists have proven to be capable of turning crises into opportunities through a phenomenon that Naomi Klein calls “disaster capitalism”. Circumventing this mechanism is both fundamental and complicated, starting from international cooperation on COVID-19 vaccine development to prevent Big Pharma from monopolizing it.

To conclude, I see two major areas of intervention to rebuild our economic system after the crisis. First, it is necessary to restore the power of public institutions and put an end to the failed laissez-faire paradigm. Economists like Mariana Mazzucato have deeply investigated how the state could be a leading actor in innovation. A state with more responsibilities would also require better public administration skills, solving the problem of charlatans-in-charge, a long-awaited objective of Western countries. Second, it is the moment to address environmental concerns by restructuring our social and economic systems. This crisis could be seen as an unexpected opportunity to do so — not to mention the end of the growth imperative, a recurrent topic in this newsletter. However, the extraordinary economic measures taken by governments should take this into account from this initial phase. The risk otherwise is to finance business as usual and slow down the Green New Deal adoption.

The restoration of a fair and sustainable economic system in which the state could have a leading role is strictly related to another fundamental topic: how do we fix democracy to make it meaningful in an age of rapid and global transformations? In the next issue, I will deepen the sudden acceleration of the drastic changes occurring to our democracies because of the coronavirus pandemic.

Alternative perspectives

📴 In an article published on Eurozine, Caroline Molloy argues that the increasing outsourcing of critical public services to digital platforms is eroding the social contract of the welfare state, especially in healthcare. Risks go beyond data governance, as Big Tech alters the natural functions of the state in unpredictable ways. Moreover, improved efficiency and accessibility of outsourced digital healthcare services are still to be proven.

This has of course been going on for a while. Those who have grown up during the era of digital neoliberalism, who have been surveilled, assessed, shoved into tickboxes and league tables in every one of their interactions with the state since childhood, may be less committed to defending the welfare state as they’ve experienced it. […] Digitalisation is often sold to us as an ally in a fight for better services for all. Indeed, it can and must be. But only if we are discerning about the claims made for it by states and corporations, and are in a position to put forward our own alternatives. We need a radical technology approach, going beyond traditional human rights approaches, that analyses the claims made for technology and asks whether its use is promoting emancipation and democracy.

📣 According to Taylor Owen, digital platforms managed to moderate content related to extreme topics such as terrorist speech or child pornography, but they find it hard to do the same with broader categories such as hate and harmful speech. In a recent article published on CIGI, the author argues that it is fundamental that markets exert more pressure on platforms to have these contents moderated, while governments should step in to define the boundaries of online content.

This is the challenge that not only governments but the platforms themselves face. The former have a growing mandate to protect their citizens online, and the latter have a business model and a design that severely limit their capacity to act. The answer, from my perspective, is global coordination on penalties for non-compliance (to universalize the costs) combined with national definitions of harmful speech (to allow for local jurisdiction). Such a coordinated response would incentivize action from the platforms while placing the responsibility on defining the limits of speech on democratic governments. The last thing we want is private companies making decisions on what speech is acceptable and what is not. But the only viable alternative is democratic government taking on this function themselves. This role will not be easy, but it is likely, over time, to become a core mandate of governing in the digital age.

Other readings

🌻 Because of coronavirus, many seasonal farmworkers from Eastern Europe are blocked at the borders with Western countries, which could make harvesting a serious issue in the EU (The New York Times).

📅 According to Joe Pinsker, there are four possible timelines to getting back to normalcy during and after the global pandemic (The Atlantic).

💻 According to Saurav Dhungana, there is a recipe for building effective data science teams (Medium).

Thanks for reading.

Please give me any feedback about this issue. If you enjoyed reading it, like and share Reshaped with potentially interested people.

Have a good weekend!

Federico