🌌 Reshaped #36

Data colonialism, consulting disruption, carbon taxes, VC records, space warfare regulation and much more

Welcome to a new issue of Reshaped, a newsletter on the social and economic factors that are driving the huge transformations of our time. Every Saturday, you will receive my best picks on global markets, Big Tech, finance, startups, government regulation, and economic policy.

This week, I dedicated a short essay to exploring why the term “data colonialism” makes little sense and why we should go beyond such a simplistic definition of modern data extraction processes. In The big picture, you will find three extremely interesting papers I strongly recommend.

But let me do some housekeeping first. In a public post on his website, our reader Sergio Caredda mentioned Reshaped among the list of “essential newsletter you should read”, with a very nice review that you can read below.

Besides the curation of external content, Federico provides every week with a high-quality essay on some exciting topics that sit between economics and other development trends.

I do not usually share the feedback I receive from readers, but this is a different story. Finding my name in a list that includes Benedict Evans, Azeem Azhar, and Alex Danco was an unexpected pleasure that motivates me even more.

If you agree with Sergio, take a moment to share this newsletter with your network!

New to Reshaped? Sign up here!

Can we call it data colonialism?

In a recent interview, the renowned historian Yuval Noah Harari commented on the incredible edge that exponential technologies like artificial intelligence generate for some states to the detriment of others.

In the 19th century there was a gap between somebody who had steamships and railroads and somebody who didn’t. But the gap between somebody who has AI and somebody who doesn’t is much bigger. In the 21st century, to make a country a colony, you don’t need to send the tanks in. You just need to take the data out. We are now seeing a new form of imperialism — you can call it “data colonialism”.

The link between colonialism and data extraction is not new. A couple of years ago, a paper reported that “data relations enact a new form of data colonialism, normalizing the exploitation of human beings through data, just as historic colonialism appropriated territory and resources and ruled subjects for profit”. But how far can we compare today’s scramble for data with historic colonialism? In this short essay, I will try to explain why the use of this term is, at best, very inaccurate.

For sure, there are some common traits that clearly emerge when comparing XVI century colonialism with the entrepreneurial age. For instance, both are technology-driven phenomena. The great nautical discoveries — including new ships like carracks and fluyts — allowed Europeans to reach African and American shores and transport more people and goods. Similarly, new mining techniques made it possible to increase the production of gold and silver. Early colonialism was sustained by a long trial and error process — no, Eric Ries did not invent iterations — in every aspect from military to diplomacy up to economic and political systems. And, like most entrepreneurs in the innovation economy, adventurers were moved by the outstanding rewards given by European monarchs in exchange for extreme risks and uncertainty.

To better understand why the term “data colonialism” is so inaccurate, let me dive deeper into the three fundamental characteristics of colonialism.

First, colonialism was about extraction. Extraction included the precious Pernambuco wood (or pau brasil) and sugar from Brazil. But it was primarily aimed at moving gold and silver to Europe. After an initial focus on African gold, silver extracted from South America represented the majority of exports (see chart below). The inflows of these metals contributed, along with population growth, to the European inflation started in the XVI century. Africa became the hotspot of another kind of extraction: the Atlantic slave trade. The accumulation and the circulation of metals were consistent with the dominant mercantilistic ideology of that time. Despite the losses of silver in the transportation process — about one third was captured by privateers or illegally distributed to local provinces — and the high war expenditures, these inflows contributed to the rise of the modern state and a new class of merchants.

Second, colonialism was driven by the willingness of monarchs to expand their sphere of influence in places where they could rearrange the dynamics of power that partially constrained their authority. The almost limitless licenses (charters or capitulaciones) granted to captains lasted until the proper establishment of extraction colonies. Later, monarchs removed many of these privileges and promoted the emergence of local classes of merchants, in opposition to powerful landlords. Similarly, monarchs had the right to nominate bishops in the colonies, which reduced the power of the Church in the New World.

Third, colonialism generated social transformations and contributed to the evolution of the Medieval class structure. Merchants emerged as the new dominant European class. In Africa, dominant classes took advantage of the slave trade to reinforce their power. For a couple of centuries at least, Atlantic relationships were limited to three types of interaction: war, diplomacy, and trade. To simplify, we might say that the winners were those who best adapted to this trichotomy — avoid war, provide diplomatic opportunities, and access trade routes. Unfortunately, the vast majority of native populations paid the highest prices. Apart from those who allied with the Europeans, either as warriors or interpreters, they were enslaved to extract silver or work in plantations — not to mention the demographic tragedy caused by diseases.

Most of these characteristics also apply to the so-called neocolonialism in the XX century. Extraction revolved around oil. The expansion of the sphere of influence was a core constituent of the cold war. And the social consequences of late colonialism are still evident in the Middle East and Central Asia.

Above all, the association between colonialism and data extraction fails to recognize that data is intrinsically different from traditional objects of extraction — included oil or gas. Differently from oil or coal — which, being rivalrous and excludable, fall into the private good category — data seems to fit better in the club good category. Indeed, data is not rivalrous: my use of it does not preclude yours. Even if state A gained access to the whole healthcare data of state B, its dominance would not be guaranteed for three main reasons:

State A could be hacked and lose its dominance much easier than Spain could lose its silver due to contraband or privateers.

State B could be hacked so that State A would not have exclusive access to data.

State B could double-cross and provide the same data to state C.

Hence, non-rivalry and the impossibility to guarantee excludability make dominance much more uncertain than in the past, when the control over key resources could only be reversed by war or long-term power shifts. By contrast, the ability to mitigate these risks would mean having access to some sort of Orwellian power that would result in world dominance.

The second element is about extraction dynamics. Data extractors are not states, but corporations. Especially in the imperialist phase in the XIX century, colonialism was about states expanding their sphere of influence overseas. In the digital age, private companies compete to gain access to whatever source of valuable data. There is no alignment between states and corporations; on the contrary, they are facing diffused backlash and growing antitrust scrutiny. The only exception is China, where this alignment is stronger and will be reinforced even more in the coming years.

This leads us to the third element. Today, the sources of data extraction processes are everywhere. There is no boundary, which makes the comparison with colonialism totally absurd. The scale of data extraction is at the same time maximum (the world) and minimum (everything we do), as perfectly explained by Shoshana Zuboff in her The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power.

This probably cannot be defined as colonialism, but we might legitimately call it a quest for dominance. And we are so used to saying that companies should pursue market dominance that it is difficult to understand where the dominance of the markets ends and that of society begins. After all, world dominance is the ideal ending scenario of any imperialism. Which, in turn, is the stage of maturity of colonialism. Therefore, it might be simply too late to call modern data extraction processes “data colonialism”.

The state

The battle between China and the US over technology is extending beyond TikTok, WeChat, or Huawei. A couple of days ago, the US government released a list of technologies that are considered critical to national security (The Wall Street Journal). The goal is to restrict exports of key technological innovations to prevent Chinese tech companies from dominating global markets. This might work in some areas, especially semiconductors, where China has always struggled to fill the gap with US producers. However, according to Craig Addison, it will take many years to do that.

China must reduce its near-total dependency on American chip tech, but it does not have a good track record when it comes to developing its own chip industry – even with the help of foreign technology partners. […] For China, fully decoupling from US semiconductor technology will require a herculean effort over many years, if not decades, but it is already off to a shaky start. […] China’s biggest challenge won’t be money — it will be finding qualified people. […] A completely new mindset may be required to come up with an alternative to the existing silicon-based chipmaking process. Materials like graphene and gallium nitride are often cited as potential replacements for silicon.

As a response, China is considering a similar move in its Export Control Law, aimed at restricting exports of key materials and technologies (South China Morning Post).

Meantime, the new World Economic Outlook Update released by the IMF forecasts a 5.2% global economic growth in 2021 and a slower 3.5% growth in the medium term. However, the resurgence of contagions worldwide is worrying policymakers. The European Central Bank (CNBC) and the Bank of England (Reuters) seem ready to lower interest rates to boost lending by banks. The latter is even considering zero or negative rates to stimulate the economy.

The markets

Management consulting

According to Quartz, job opportunities for aspiring management consultants are declining. After the shock caused by the pandemic, the sector’s hirings have recovered more slowly than the overall economy (see chart below).

A new report by CB Insights dives deeper into the disruption that is hitting most management consulting companies, including the industry leaders McKinsey, BCG, and Bain.

Management consulting is primarily human-driven. Hourly or per diem billing, rather than outcome or value-based pricing, is still the general rule (even as industries like law move away from billable hours). The increasing pace of technological change means that, more and more, consultants’ recommendations are out of date nearly as soon as they’re made. Consulting, in other words, is inefficient, inflexible, and slow to adapt. Any of these weaknesses alone would suggest coming disruption — possessing all of them points to a major fight ahead.

If you work in management consulting, you may have heard something similar before. However, the sector always managed to adapt to new factors of disruption thanks to three main factors: extreme organizational flexibility, reputation, and participation in the strategic planning process. The latter is particularly important: through consulting and research services, management consulting companies have the chance to influence the strategy of their client companies and leave a door open for a future need for their services. The chance to buy time so easily is an incredible competitive advantage for major players in the sector.

Social media

In a recent poll on LinkedIn, the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI) asked its followers an apparently simple question: should big tech be setting the terms of political speech? While I am writing, only 16% answered it should. But what if we reframe the question? Something like: should big tech limit disinformation related to major electoral events? I suppose that the result would be different — probably not that much, but different.

The problem is that the distance between managing content and setting the terms of political speech is hardly measurable or quantifiable. Hence, it is hard to regulate it. A recent essay by Andrew Marantz in The New Yorker examines the complex dynamics behind how Facebook handles misinformation and hate speech. This is my pick of the week, a brilliant piece of journalism I definitely recommend.

It is possible that Facebook, which owns Instagram, WhatsApp, and Messenger, and has more than three billion monthly users, is so big that its content can no longer be effectively moderated. Some of Facebook’s detractors argue that, given the public’s widespread and justified skepticism of the company, it should have less power over users’ speech, not more. […] In retrospect, it seems that the company’s strategy has never been to manage the problem of dangerous content, but rather to manage the public’s perception of the problem.

The speculators

Venture capital

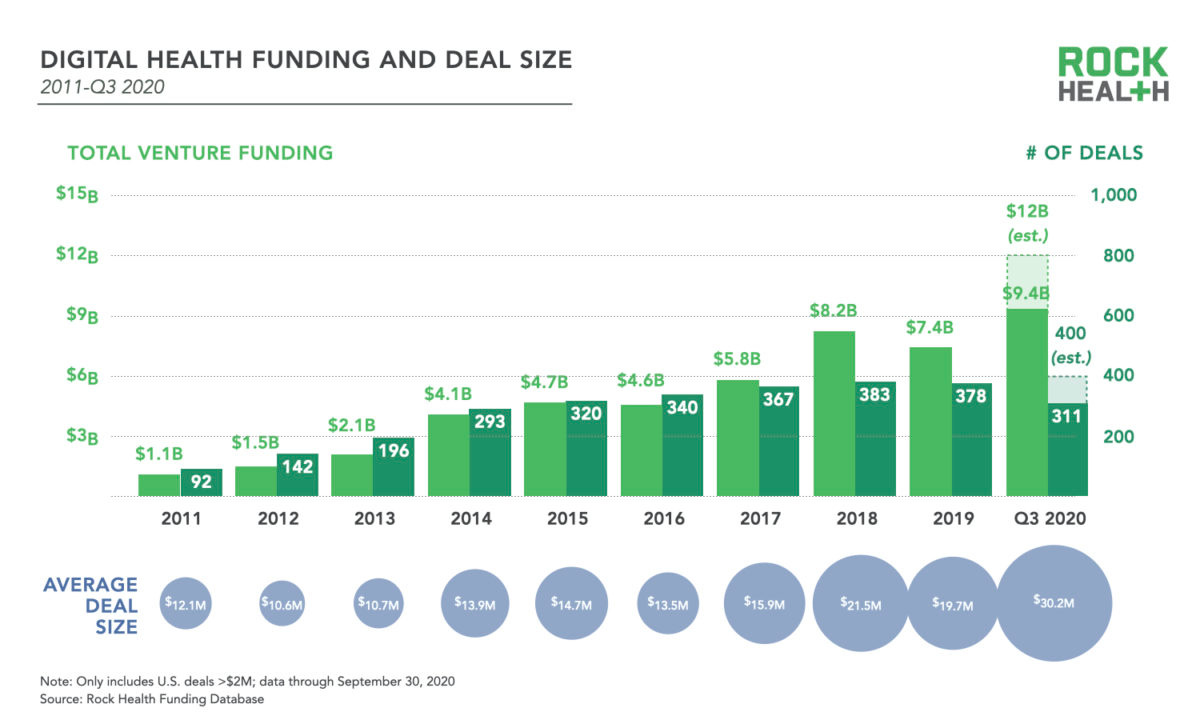

The Q3 2020 MoneyTree report by PwC and CB Insights provides interesting insights on VC trends in Q3. The chart below shows a 40% rise in global VC funding relative to Q2 — which reflects the hot summer of VCs all around the world. In the US, Q3 also set a record for the largest number of megadeals, with 88 deals worth $100M or more.

A particularly interesting sector is digital health, which hit a new record in the US, where “the stock market’s sharp recovery and pandemic-initiated policy and regulation changes have enabled large competitive moves and commercialization activities”. With an expected total venture funding of $12 billion and 400 total deals, the industry seems well-positioned to disrupt the healthcare sector, especially in fields that can benefit from the shocks caused by the pandemic like virtual care delivery.

SPACs

For SPACs, this is already a record year (see picture below by Bloomberg). New deals are announced every day in the most diverse sectors, from aerospace to software up to biotech and gaming. It should not come as a surprise that SoftBank is joining the SPAC wave with its own blank check acquisition company (Axios). The company will be financed through a mix of SoftBank’s own capital and external funds and will focus on tech acquisition opportunities.

By the way, according to The Information, this is not particularly far from SoftBank’s main business.

[…] SoftBank is an investment firm that raises cash to invest in or buy businesses. Sounds a lot like what a SPAC does. This seems just another opportunity to raise cash for SoftBank. The danger, with so many SPACs chasing deals, is that the quality of deals will decline. SPACs may end up overpaying for businesses just to get a deal done. Just one disastrous deal would be all that’s needed to kill the SPAC frenzy.

In analyzing SPACs, we should also take into account that they can serve two different needs. On one hand, they provide an alternative path for companies willing to go public through an IPO. However, the most hyped startups might be strong enough to take the main road and go public independently — that is the case of Airbnb, which refused to join Bill Ackman’s SPAC last month (CNBC). On the other hand, SPACs can try to convince more traditional private companies to join them and go public. Both scenarios can easily reduce the quality of the deals, because target companies would be either not-so-good startups or companies that do not fit public markets performance requirements.

ESG investing

A recent paper explores some controversies of socially responsible companies. In particular, there are three areas of concern. First, these companies “commit environmental and labor-related compliance violations more often (and pay more in compliance penalties)”. This should negatively impact at least the E and the S of their ESG score. Second, they “spend more on lobbying policymakers and receiving more in targeted government subsidies”. This is evidently a governance issue. Finally, their CEOs “receive higher abnormal compensation” while their boards are composed of few independent directors.

This sheds light on ESG investing. The analyzed sample of ESG funds “contain portfolio firms with poorer labor and environmental track records, spend more on lobbying and receive larger state subsidies relative to portfolio firms in non-ESG funds”. This is consistent with what I wrote months ago on this issue: ESG funds are not here to save the world. At most, they will put more pressure on sustainability as a key strategic goal for corporations.

The purpose of those funds is to apply environmental, social and governance lenses to traditional investing. In other words, fund managers first identify high-potential stocks in line with their investing strategy and then make their final choice depending on the ESG rating of the companies.

The big picture

The economics Nobel awarded to Paul Milgrom and Robert Wilson for their studies of auction theory generated some critiques among those who consider the subject far from what the world would need in such a complex situation. However, this is an extremely naive point of view. On Nature, Philip Ball provides some interesting insights about the many areas of application of their theories, which go far beyond typical auctions and include “applications ranging from the pricing of government bonds to the licensing of radio-spectrum bands in telecommunications”.

I am leaving you with some reading recommendations.

A recent ECB working paper explores “the optimal design of a carbon tax when environmental factors, such as air carbon dioxide emissions (CO2), directly affect agents’ marginal utility of consumption”. The authors found that the optimal carbon tax is determined by the implicit market price of CO2 emissions and is thus pro-cyclical. This means that policymakers can “use the carbon tax to ‘cool down’ the economy during periods of booms and to stimulate it in recessions”. The paper is technically complex but definitely worth reading.

A working paper released by the SPRU at the University of Sussex analyzes the relationship between innovation and development banking. The author found a positive relationship between innovation intensity in Brazil and public funding from the Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social (BNDES). Development banks are often under attack for crowding-out private investment opportunities and picking winners. For this reason, clarity about how they support entrepreneurship and innovation processes is a fundamental research goal.

In a new paper, Eytan Tepper observes that scarce and old laws regulate space warfare, which is growing in importance as governments and private companies invest more in the space economy. However, according to the author, trying to revitalize a multilateral system could not be the ideal solution. Instead, “policymakers should embrace and facilitate a decentralized governance system and divert governance-building efforts to be invested in various small-scale initiatives”, mainly because “decentralized governance is more feasible and efficient than a centralized multilateral system”.

Thanks for reading.

As always, I am waiting for your opinion on the topics covered in this issue. If you enjoyed reading it, please leave a like (heart button above) and share Reshaped with potentially interested people.

Have a nice weekend!

Federico