🌌 Reshaped #34

New missions for Horizon Europe, Q3 record in M&As, wealth defense industries, SaaS startups' direct listings and much more

Welcome to a new issue of Reshaped, a newsletter on the social and economic factors that are driving the huge transformations of our time. Every Saturday, you will receive my best picks on global markets, Big Tech, finance, startups, government regulation, and economic policy.

This week, I am happy to share some updates about Horizon Europe and its mission-oriented structure. Mission-oriented innovation is one of Reshaped’s hot topics and one I can hardly be neutral about. I am also covering the most recent updates coming from public and private markets, which will have huge implications on the rewarding system of the innovation economy for months to come.

Please, take a moment to share this newsletter with your network!

New to Reshaped? Sign up here!

The state

Mission-oriented innovation

The EU is starting to unveil the details of Horizon Europe, the €100 billion research and innovation programme that will replace Horizon 2020 starting from next year. Like it predecessor, it will be structured in vertical clusters reflecting some of the key areas of the EU strategy for innovation (see the Pillar 2 in the picture below).

Horizon Europe is an effot to put in practice a mission-oriented innovation strategy in the EU, catalyzing the many actors of the European innovation ecosystem towards some shared goals. Last week, the European Commission announced the launch of five distinct areas that will be addressed through missions:

Adaptation to climate change including societal transformation

Cancer

Climate-neutral and smart cities

Healthy oceans, seas, coastal and inland waters

Soil health and food

Using the terminology introduced by economist Mariana Mazzucato (for a primer on her positions, see this recent article on Foreign Affairs), who managed to bring back mission-oriented innovation into the political discourse, we could call these areas “grand challenegs” (see picture below, taken from one of her reports). Missions set strategic goals to effectively address these challenges and, in turn, they are structured in many different projects that explore different approaches to reach these goals. Mission projects are structured as bottom-up attempts to find a standard for solving the challenge; hence, most of the competition between the actors of the European innovation economy will take place there.

Each mission will have a board and an assembly that will “help specify, design and implement the specific missions [I suppose it is an inaccurate simplification for mission projects] which will launch under Horizon Europe in 2021”. In particular, these actors will have to coordinate the three pillars around which, according to Mazzucato, a mission is structured: citizen engagement, public sector capabilities, and finance and funding. The latter is a relevant area of improvement for the EU with respect to Horizon 2020, which has been heavily criticized for the structure of consortia and the management of public funding.

Another area of concern, as reported by Science, is the presence of non-research voices in the budget.

The fact the missions won’t focus exclusively on research has raised concerns that some of Horizon Europe’s budget might be diverted from research, although the missions could receive additional funds from other programs. “The key concern is that these were always supposed to be R&I [research and innovation] missions,” Palmowski says. “There’s a lot of non-R&I content in there.” He says another concern is that the plans focus on applied research, leaving little room for basic science. Partially agreed legislation would limit the missions’ share of Horizon Europe—for the first 3 years—to 10% of the program’s targeted top-down pillar. The size of that pillar hasn’t yet been agreed, but it could be more than half of Horizon Europe’s total budget.

In other words, the EU will not only finance the upstream side of innovation (such as basic research), but also the downstream. Even if I agree with the principle behind this concern, I must admit I would be worried to see a lack of attention to applied research and innovation adoption in the new program. The risk, of course, is that Horizon Europe will translate into a myriad of projects with scarce potential for application. It will be crucial to mitigate that risk through a control-and-reward system maximizing both generation and diffusion of innovation spillovers.

I will return on Horizon Europe as soon as more information about it is released. In the meantime, take a look at this recent paper by Benjamin F. Jones and Lawrence H. Summers on the many societal benefits of investments in innovation and the many spillovers it generates. In addition, I recommend this report by the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change on how to reconfigure “the operational model of the state so that it looks more like a modern, tech-enabled institution and less like a 20th-century bureaucracy”.

Antitrust

On The New York Times, the economist Austan Goolsbee warns against a coming wave of consolidation in the US, driven by the fact that “during the extended economic crisis created by the coronavirus pandemic, many large companies — and especially their stock market values — have been growing rapidly while their small business competitors have faced something of an apocalypse”. However, stricter antitrust regulation is hampered by three main factors: the enforcement budget for antitrust actions that is decreasing over time, the so-called “failing firm defense” that permits takeovers if the acquired firm is going to die anyway, and the tendency to weaken antitrust regulation in times of crisis.

However, antitrust scrutiny for US corporations is not only a domestic matter. This week, Alphabet got a green light about the acquisition of FitBit by EU authorities in a move that will reshape the wearable competition landscape (Barron’s). At the same time, China is ready to file an antitrust suit against Google, accused by Huawei of exploiting the dominance of its Android system to damage competitors (Business Insider). Meanwhile, in China, the Communist party is goint to exert greater control over private business (Financial Times).

China’s private sector still accounts for 50 per cent of government tax revenues, 60 per cent of economic output and employs 80 per cent of all urban workers. This is despite years of systemic discrimination, such as limited access to bank loans compared with their state-owned peers. Under the new guidelines, party committees that previously wielded little power at private companies are supposed to play a role in personnel appointments and other important decisions.

The markets

Mergers and acquisitions

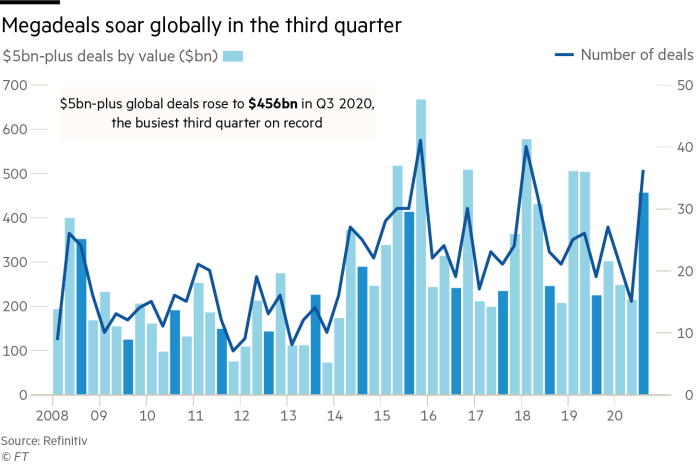

As already covered in previous issues, this summer will be remembered as one of the most active in business dealmaking. The third quarter of 2020 has been extremely productive in terms of M&As, with a combined value of $456 billion (Financial Times). This is not only a record for a third quarter but also a decisive turnaround with respect to the negative trend that started in Q4 2019. This translates into a great opportunity for investment banks. In Q3 alone, “Wall Street banks booked a record $28bn in investment banking fees, bringing their year to date total to $89bn”.

Half of these deals come from tech companies, which account for $226 billion in total M&As in the third quarter. The most relevant of them was finalized three weeks ago with the acquisition of Arm by Nvidia. Biotech and pharmaceutical M&As were also on the rise, with the acquisitions of Immunomedics, Livongo, Varian, and Momenta by Gilead, Teladoc, Siemens, and Johnson & Johnson respectively. As already discussed, three main factors have contributed to the spike in M&A deals: the race to quickly adapt to the post-pandemic trends and acquire an edge over competitors, the spread of SPACs that are reshaping the way companies go public, and the availability of huge cash reserves among tech giants.

Management consulting

A new paper by Lena Ajdacic, Eelke M. Heemskerk, and Javier Garcia-Bernardo analyzes the relationship between the Big Four audit and management consulting companies (Deloitte, PricewaterhouseCoopers, Ernst & Young, and KPMG) and the aggressive tax planning strategies implemented by their customers. According to the paper, auditors from these companies “trace legislative changes across countries, design and promote legal, accounting and financial vehicles to overcome national boundaries by carefully placing assets and liabilities in specific jurisdictions”.

Governments struggle to find a balance between attracting foreign investments and fighting these attempts to overcome domestic taxation. These goals are in contrast with each other, which gives corporations even more power in this process. This is why the authors define this set of activities as a “Wealth Defence Industry”. In it, big accounting and auditing companies have a competitive advantage relative to their smaller competitors.

The design of wealth defence schemes requires extensive expertise on international law, accounting, and tax regulation. The Big Four accountancy firms (PwC, Deloitte, EY and KPMG), which dominate the accountancy market, are better positioned to deliver these services than their smaller competitors. First, their size enables them to reach a higher level of knowledge intensity (Von Nordenflycht 2010). This is rewarded by companies, which rely on expertise regarding corporate structures, international law and taxation. Second, the widespread geographic presence of the Big Four auditors enhances their knowledge about strategies which span multiple countries. It strengthens their capacity to get access to authorities in advantageous jurisdictions and moreover enables the spread of new products across a large network of offices to clients.

The speculators

This week, the schedule of hyped tech IPOs came to an end as Palantir and Asana went public (The New York Times). Palantir opted for a direct listing, which was a success “despite its inability to turn a profit and the many controversies swirling around it”. The company was valued at $21.4 billion by public markets, slightly above the last private valuation of $20 billion. Asana also went public through a successful direct listing that provides some interesting insights on SaaS startups and their fundraising strategies (TechCrunch).

Asana’s results augur well for other SaaS startups that may not find the traditional IPO process enticing but don’t want to wager their public debut on more exotic mechanisms like blank-check companies, especially the bulk of late-stage SaaS unicorns that are still cash-hungry and far from profitable on a GAAP basis. Asana’s debut, then, is a lit torch for late-stage SaaS startups that have access to private cash and want to trade publicly.

A recent article by The Information observes that these recent direct listings brought a reduction in the gap between public and private valuations with respect to the more notorious ones undertaken by Spotify (2018) and Slack (2019). The former traded at a 9% premium, while the latter did it at a 20% premium relative to the private market high before listing (see chart below). The increased alignment in private and public valuations means that direct listings will serve less as a way to profit from market premiums and more as a fundamental fundraising opportunity for startups with a positive track of private rounds.

However, as reported by Quartz, the gap in stock holdings between the richest 10% and the rest of US investors has widened (see chart below). While these top investors continued to grow their stock holdings despite the impact of fluctuation in the 2000s, “the average estimated stock holdings of the least wealthy 25% of Americans actually went down from $8,100 in 2016 to $6,400 to 2019”. The incredible increrase in the gap between the top percentile and the others is a worrying sign of the growing elitism of stock markets and an indicator of the failure of trickle-down flows in the economy. This point is reflected in a recent study by Carter C. Price and Kathryn A. Edwards, who carefully analyze the growing inequality in income distribution between 1975 and 2018.

The big picture

A new article published in the last issue of Nature provides new insights about the dynamics of climate change. In particular, the authors highlight the hysteresis behavior of the Antarctic ice sheets, for which past conditions still have an impact on the present.

The ice sheet’s temperature sensitivity is 1.3 metres of sea-level equivalent per degree of warming up to 2 degrees above pre-industrial levels, almost doubling to 2.4 metres per degree of warming between 2 and 6 degrees and increasing to about 10 metres per degree of warming between 6 and 9 degrees. Each of these thresholds gives rise to hysteresis behaviour: that is, the currently observed ice-sheet configuration is not regained even if temperatures are reversed to present-day levels. In particular, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet does not regrow to its modern extent until temperatures are at least one degree Celsius lower than pre-industrial levels. Our results show that if the Paris Agreement is not met, Antarctica’s long-term sea-level contribution will dramatically increase and exceed that of all other sources.

You can find a more detailed explanation of this phenomenon in the video below.

On the impact of human activities on the planet, do not miss the recent article by Lucas Stephens, Erle Ellis, and Dorian Fuller (Aeon).

Thanks for reading.

As always, I am waiting for your opinion on the topics covered in this issue. If you enjoyed reading it, please leave a like (heart button above) and share Reshaped with potentially interested people.

Have a nice weekend!

Federico