🌌 Reshaped #31

Welfare reforms (part 1), semiconductor industry peculiarities, German green bonds, Keynesian economy, the myth of small business and much more

Welcome to a new issue of Reshaped, a newsletter on the social and economic factors that are driving the huge transformations of our time. Every Saturday, you will receive my best picks on global markets, Big Tech, finance, startups, government regulation, and economic policy.

This week I am starting to explore the difficult topic of welfare reform; after this introductory first part, I will follow up with a second one dedicated to startups and their role in the definition of such a welfare system for the XXI century. The rest of this issue is dedicated to other interesting topics like green finance, the semiconductor industry, meritocracy, and the growth of private equity in China.

Please, take a moment to share this newsletter with your network!

New to Reshaped? Sign up here!

New welfare for a new society (part 1)

Hilary Cottam, the author of the renown book Radical Help: How we can remake the relationships between us and revolutionise the welfare state, has authored a new policy report of the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose that analyzes the social and economic reasons behind the need for a new welfare system, which she calls “Welfare 5.0”. In the report, Hilary Cottam explains why “investment is needed in the creation of a new social settlement — one that can address the very different social, economic technological and ecological crises of today”.

The need for such a shift in how we design and execute welfare policies is justified by the radical changes that have occurred since the original welfare state was conceived. Rising inequalities and periodical shocks like the COVID-19 pandemic make existing welfare schemes inappropriate and ineffective on a large scale. What was working half a century ago, in the post World War II world, no longer captures the needs of a global society struggling to identify a path towards progress.

Differently from then, now “we are challenged by a new technology revolution; we face an ecological emergency of devastating proportions; we are burdened with new illnesses of the mind and body; our education systems are failing the majority; we lack care and good work; we have different expectations and social structures; we have growing inequality and new forms of poverty; and slowly, painfully, we are becoming aware of the biases inherent in so many of our post-war systems which leave the needs of many unattended”.

The latter is particularly relevant when talking about welfare reforms. I usually refer to is as “skeptical pessimism” to identify a mental condition of young generations approaching public policy and social reform. And it is strictly related to the concept of “millennial socialism”, perfectly analyzed by Lisa Adkins, Melinda Cooper, and Martijn Konings in a recent essay that covers the basic concepts of their upcoming book The Asset Economy (Los Angeles Review of Books). (This is a short and very recommended reading for the weekend!)

In the essay, the authors analyze the reasons behind the attractiveness of socialist ideas and political projects among millennials. In doing so, they refuse the common argument of a generational divide and claim that this diffused resentment of younger generations is mainly due to the economic policies like quantitative easing that favor those who currently own assets so that “the ‘rentier function’ has become embedded across social life at large”. In other words, the benefits of being an asset owner are increasing, while the possibilities to access asset ownership — that is, to access the middle class — are decreasing. This is why, according to the authors, “this new logic of inequality has mixed ‘hypercapitalist’ logics of financialization with ‘feudal’ logics of inheritance to reshape the social class structure as a whole”.

The relationship between someone’s familiar assets and its chances to accumulate new ones is increasing in the Western world, pushing those who are left behind this unequal scheme to embrace socialist ideas. And this is not fully compensated by labor or redistributive policies, as “the key element shaping inequality is no longer the employment relationship, but rather whether one is able to buy assets that appreciate at a faster rate than both inflation and wages. Employment remains an important factor as it shapes the ability to do so (e.g., the ability to service a mortgage), but it is increasingly only one among other factors”.

Hence, Hilary Cottam is definitely right to argue that there is not only one model of welfare state and to demand some radical reform of it. This was already addressed by Gøsta Esping-Andersen in his seminal book The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. In the book, the Danish sociologist distinguished between three types of welfare states: liberal, conservative, and social democratic. The main difference between them lies in their degree of de-commodification, “a process when a service is rendered as a matter of right, and when a person can maintain a livelihood without reliance on the market”.

If the de-commodification degree is low, like in the United States, welfare is often limited to basic assistance, while market forces are left free to operate in many sectors of the economy. Southern European countries like Italy or Spain have adopted a more conservative (corporatist) degree of de-commodification, while Northern European countries like Sweden have gone even further, building the most advanced capitalist welfare models of the XX century.

The post-COVID reference model for the welfare state should find a balance between the self-destructive tendency of capitalism to commodify the whole spectrum of the economy and the need for a more equal distribution of wealth and opportunities. The exponential age paired with the characteristics of the abovementioned asset economy can only make existing inequalities even more radicated in our society. But how should this process take place?

Hilary Cottam’s model builds around three priorities: reframing the pre-COVID narrative by “offering a vision of a more equitable future”, favoring a transition to a sustainable society, and working to reframe the “structural and spatial socio-economic divisions” of our societies. Too generic? Maybe it is. But it addresses two key areas of improvement: the necessary intervention of the state in the new technological revolution to determine positive social outcomes and the need to operate at the local level to regain trust and build bottom-up development processes.

But what is the role of the other actors of the innovation economy in this context? How can startups be a positive player in the quest for a new welfare model — if they ever can? And what about the role of private equity and venture capital in promoting downstream investments aligned with those ambitions? These are some of the topics that I will cover next week in the second part of this excursus on welfare.

The state

France will allocate €7 billion ($8.4 billion) on digital investments, out of the €100 billion ($120 billion) stimulus package planned to make the domestic economy recover from the coronavirus shock (TechCrunch). Part of this sum will be spent on startups through the Banque Publique d'Investissement (Pbifrance) acting as a traditional VC. This makes sense: the French government wants to prevent domestic startups from abandoning the country or, even worse, going bankrupt after the huge investments in the tech ecosystem undergone in the last decade.

Some months ago, France had already allocated some of its emergency budget to save startups from the negative effects of the pandemic. At that time, I had strongly criticized these financial aid schemes in a dedicated issue. However, this time is different: France is directly investing in the downstream application of its upstream investments (R&D). By investing directly in promising ventures, the government not only safeguards its assets while increasing its control of them; it also keeps the backed ventures closer to its economic fabric by acting as a sort of development banking actor.

At the same time, on Wednesday, Germany issued its first green bond, which “attracted more than €33bn of bids for up to €6bn of 10-year debt” (Financial Times). The trend of adoption of green bonds is extremely positive (see chart below), reflecting the increasing popularity of ESG investments.

The green bond is attracting some criticism among those who view it as a branding measure more than a financial stimulus towards green growth. And, of course, it is true that, in order to achieve the ambitious sustainability goals that most European countries have set, almost all financial resources should be dedicated to this mission-oriented kind of investment. But the German green bond is a genuine piece of good news for at least two reasons.

First, it will set a reference model for other European countries that will adopt such a measure later on. In particular, I am referring to pricing mechanisms and secondary markets, allocation of funds, and green growth strategies. Second, it will foster some form of competition among European countries willing to be at the forefront of green finance, line France and Sweden.

The markets

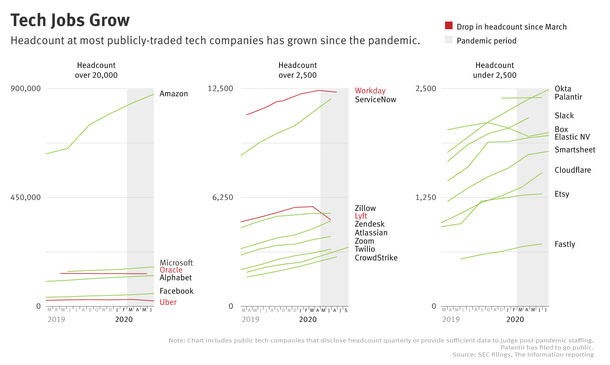

While global markets are suffering from the closing gap between Wall Street and the real economy, tech companies register positive job growth since the start of the pandemic (The Information). In the last issue, I reported a statistic showing that tech corporations are becoming the best employment solution for MBA graduates. However, if you look at the third chart below, this is a trend that applies also to smaller tech companies with less than 2,500 employees.

Among Big Tech giants, the growth of Amazon’s workforce is impressive, reflecting the dominant position that the company is acquiring inside its competitive category. The recent analysis by Benedict Evans on Amazon’s profitability is a highly recommended read to grasp the logic behind its financial statements. The multi-business nature of the company and its cash is king credo — Amazon “is run for cash, not net income” — help to see the real financial value generated by Amazon in a much more precise way.

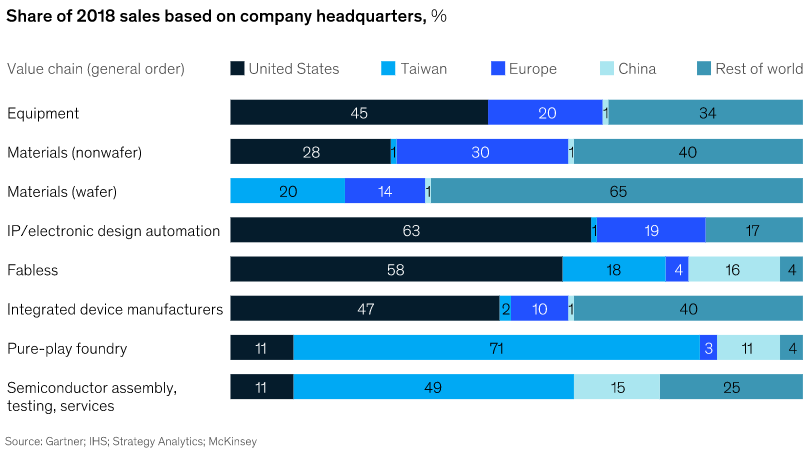

But, while the sales of Google’s Chromebooks are increasing at an incredible pace and Microsoft prepares to offer subscription plans for Xbox users, what is the future of the semiconductor industry? A new report by McKinsey brilliantly explores the inner peculiarities of the chip sector, characterized by growing demand, especially for smaller chips. Nonetheless, R&D and manufacturing costs are also very high for chips under 7 nm, which determines a winner-takes-all market, accessible only to top performers that can exploit operational excellence, solid supply chains, and economies of scale.

If this makes the market particularly hard for new entrants, the competitive scenario is not easy for incumbents as well. All of them have to choose whether to specialize in one product segment or one particular step of the value chain; otherwise, R&D costs would be unsustainable. This has three main consequences. First, it reduces the risks of oligopoly by boosting R&D expenditure — take the Intel-Apple case: no one wants to lose high-end customers. Second, it fosters the development of regional hubs specialized in a specific product or part of it (see chart below). Finally, it generates strong interdependencies that make supply chain bottlenecks particularly worrying in times of crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

The speculators

On Monday, SoftBank shares drop by 7.2% after the conglomerate “made massive bets on high-flying technology stocks using equity derivatives — and despite one report that it has billions in paper gains” (Bloomberg). After the massive fall in market cap suffered in March, Masayoshi Son managed to recover investors’ trust by generating huge gains from the sale of stocks such as T-Mobile and Alibaba. However, investors are more prudent than in the past and fear new WeWork-style investments. For such a reason, they are looking with increasing skepticism at SoftBank’s bet in the derivatives market. Some even said that Masayoshi Son resembles more to a speculator than a visionary investor.

Apart from Son’s reputation, trust in private equity instruments is increasing in the Far East. A new report by McKinsey explores the recent trends of PE investments in China, a market made hard for PE companies by state ownership and a historical preference for corporate M&As. The picture below shows that Chinese PE companies are attracting funds at a faster pace than venture capital and real estate/infrastructure. In particular, these funds are concentrated in buyout operations.

Meantime, on the other side of the Pacific Ocean, Eric Ries, the author of the bestseller The Lean Startup, announced the launch of the Long Term Stock Exchange (LTSE). Such a market for shares of companies that refuse to adhere to short-termism was already envisioned by Ries in his book nine years ago. However, the practical implementation of this vision might be harder than expected. Will a new stock market index help to support long-term investments if investors continue to seek short-term gains? And which kind of impact will such an initiative have on the VC industry as a whole, pursuing easy exits more than ever? The balancing factors mentioned by Ries seem to be quite optimistic in that sense (Quartz).

The big picture

I dedicated the last issue to exploring the key elements defining the trade war between China and the United States. I received positive feedback from some of you and an invitation to include this kind of contextual topics in future issues. To dive deeper in the Chinese attempt to gain regional dominance in the Far East, see the recent analysis by Elbridge Colby and Robert D. Kaplan on Foreign Affairs.

This week, I will leave you with three provoking recommendations. First, a keynote speech by Robert Skidelski at the annual conference of the European Association for Evolutionary Political Economy (EAEPE). Much has been said about the need for Keynesian policies to address the post-COVID needs of our economies, and no one knows the meaning of “Keynesian” better than Professor Skidelski. According to him, three main changes affected the world after the death of Keynes: globalization, rising inequalities, and climate change. New Keynesian policies cannot avoid confronting them, but they need to stick around the idea that state intervention is needed to make free markets work properly.

Second, an article by Robert D. Atkinson and Michael Lind that analyzes some of the key topics of their book Big Is Beautiful: Debunking the Myth of Small Business. The authors dismantle the myth that small businesses (including startups) are superior — from organization to morality — with respect to large businesses.

According to the logic of small business advocates, society should favor firms when they are small, but as soon as they add their 501st employee, they become the object of indifference or even derision. This is as perverse and unhealthy as the attitude of parents who hope that their children will never grow up. […] But what about startups, the supposed source of American economic renewal? It turns out that most startups don’t actually create that many jobs either.

This is very relevant for countries that heavily rely on SMEs for job creation and GDP growth, like Italy, where the debate about the productivity of these companies is often biased and inaccurate.

Finally, a piece by Michael J. Sandel on The New York Times, in which the famous political philosopher explains why “disdain for the less educated is the last acceptable prejudice”. This is a very current topic all around the Western world, where old elites struggle to communicate with those voters who endorse populist parties or conspiracy theories.

Building a politics around the idea that a college degree is a precondition for dignified work and social esteem has a corrosive effect on democratic life. It devalues the contributions of those without a diploma, fuels prejudice against less-educated members of society, effectively excludes most working people from elective government and provokes political backlash.

Sandel’s article also elegantly points the finger at the so-called “meritocracy trap” to recognize the role of luck — which I read as chance — in shaping careers and lives.

Appreciating the role of luck in life can prompt a certain humility: There, but for an accident of birth, or the grace of God, or the mystery of fate, go I. This spirit of humility is the civic virtue we need now. It is the beginning of the way back from the harsh ethic of success that drives us apart. It points beyond the tyranny of merit toward a less rancorous, more generous public life.

Thanks for reading.

As always, I am waiting for your opinion on the topics covered in this issue. If you enjoyed reading it, please leave a like (heart button above) and share Reshaped with potentially interested people.

Have a nice weekend!

Federico