🌌 Reshaped #14

The "right" kind of AI, French digital taxation, American semiconductors, M&As under coronavirus and much more

Welcome to a new issue of Reshaped, a newsletter for those who do not want to miss a thing about the huge transformations of our time.

In this issue, I will discuss a recent paper on AI and automation: is there a “right” and a “wrong” way of conceiving AI? How to make it work for society as a whole? Which relationship does it have with universal basic income?

For a daily review of the most relevant news from the world of startups and venture capital, I strongly recommend you to follow The Dart, a new initiative of our readers Matthieu Crétier and Francesco Fontana.

Do not forget to share Reshaped with your friends and colleagues!

New to Reshaped? Sign up here!

News

Business and Finance

🍔 Uber Eats is considering the acquisition of rival company Grubhub to challenge the US market leader DoorDash (Forbes). According to analysts, the new company would control more than half of the American food delivery market, which is growing fast due to lockdowns. The move is particularly relevant for Uber, whose main business is worryingly shrinking.

🎬 Amazon was linked with the acquisition of the movie theater chain AMC Entertainment, which was heavily affected by shutdowns (Daily Mail). Clearly, the move is aimed at making Amazon Prime Video stronger. However, the growing uncertainty around the future of cinemas means it will take longer to see returns on such an investment (Observer).

🚗 Waymo raised an additional $750 million in its first external fundraising round, which now totals $3 billion. Autonomous vehicles are facing tremendous deadlocks, but CEO John Krafcik believes that COVID-19 will benefit the industry (The Verge).

🎧 Apple acquired NextVR, a startup specialized in creating sports content for VR headset, a business Apple wants to explore further to strengthen its TV segment (Bloomberg).

💶 French Economy and Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire announced that France will implement a digital tax on tech corporations even if no international agreement is reached in the EU and within the OECD (Reuters). I cannot be neutral on that: this is not only an important economic decision, but also an enormous political step towards fairer redistribution of wealth. This is even more pressing during the current global emergency — especially because revenue disclosures show how resilient is Big Tech to the economic downturn.

💻 The US government and American semiconductor companies are working together to increase chip production in the country in order to reduce the dependency on Chinese supplies (The Wall Street Journal).

Science and Technology

🐾 Veterinary telemedicine company VetNow and Smithsonian scientists are partnering to detect animal disease outbreaks remotely to intervene before humans can be affected (Fast Company).

🌿 Thanks to microalgae, an Australian team of scientists believes it is possible to make coral reefs more resistant to heat caused by climate change, reducing bleaching effects (BBC Science).

👀 In a new experiment, scientists used electrodes to stimulate the brain of blind people to “see” letters that in reality did not exist, which could open new possibilities to advance research in the field (Scientific American).

🦇 By pushing animal species to move from wild areas to more human-dense places, climate change can influence the spread of diseases like COVID-19 (Carbon Brief).

💡 The “right” kind of AI

In a new discussion paper, economists Daron Acemoglu — co-author of bestsellers Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (2012) and The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty (2019) — and Pascual Restrepo contribute to the debate on automation with an interesting, fresh perspective. Their analysis starts from an often underrated question: is the current direction of AI (more automation) the best way to increase productivity and develop societies? The abstract of the paper is reported below.

Artificial Intelligence is set to influence every aspect of our lives, not least the way production is organized. AI, as a technology platform, can automate tasks previously performed by labor or create new tasks and activities in which humans can be productively employed. Recent technological change has been biased towards automation, with insufficient focus on creating new tasks where labor can be productively employed. The consequences of this choice have been stagnating labor demand, declining labor share in national income, rising inequality and lower productivity growth. The current tendency is to develop AI in the direction of further automation, but this might mean missing out on the promise of the “right” kind of AI with better economic and social outcomes.

In short, automation works well when new labor is generated thanks to the transformation of economic systems, which is reflected in new jobs and new business sectors. In the last two decades, this did not happen: productivity has faced a terrible stagnation, while employment levels and average wages have decreased. The promise that automation would replace workers while providing economic gains for society as a whole remained on paper. Even more, this replacement did not always occur in the riskiest functions or activities, especially when offshored in developing countries.

Acemoglu and Restrepo claim that automation without counterbalancing measures to sustain labor demand leads to sluggish growth and social disorders — and, in particular, to greater inequality. Moreover, when AI is applied to replace tasks that are already well-performed by humans, productivity gains might be little or even negative. This last point is extremely important as it forces us to think about the application of AI with an approach based on systems thinking. Basically, we should keep in mind that replacing humans with machines could result in suboptimal results when that generates the effects that three decades ago Lisanne Bainbridge defined the “ironies of automation”.

Instead, AI should be designed and applied to generate huge benefits for society. If this cannot happen with an automation-based approach to AI, a shift is required

to restructure the production process in a way that creates many new, high-productivity tasks for labor. If this type of “reinstating AI” is a possibility, there would be potentially large societal gains both in terms of improved productivity and greater labor demand (which will not only create more inclusive growth but also avoid the social problems created by joblessness and wage declines).

Acemoglu and Restrepo argue that market forces would have little incentives to switch from the “wrong” to the “right” kind of AI. And this time state intervention might not be enough to compensate for externalities and market failures.

In the meanwhile, the debate on automation and the future of work has devoured the one on universal basic income (UBI). The rationale is simple: automation is defined as inevitable — inevitability is the strongest component of any contemporary narrative of technology-driven social and economic change — and, even if there is a chance that new jobs will be created, the economic system might adapt too slowly and leave millions out of the labor market. Hence, we need a UBI to compensate for job loss.

It is not a case if UBI as a solution for the collapse of labor demand is strongly sponsored by billionaires and financial elites. They would retain the total control of production with little to worry about unionized workers; governments would have to care about the masses of unemployed people and the enormous societal transformations that would stem from such a situation. Those blessed with optimism will say that fiscal policies will be designed to fairly address the need for huge public spending. After all, someone will have to take care that citizens continue to be consumers.

However, realism tells a different story. With production in the hands of business elites and income distribution in those of political leaders, citizens would simply be consumers, with little to no impact on productivity and development. Somebody would decide how much you get at the end of the month, with no linkages on your productivity. A more pessimistic view would easily conclude that this would be the end of democracy — even if it is important to remember that fears of automation and mass job losses have been around for centuries and are still utopias. Curiously, the “right” kind of AI suggested in the paper would not only help to avoid such a scenario; it would also mitigate the negative consequence of already implemented automation.

To conclude:

Automation is not the only path for AI, which can be the technology platform that helps to build better productive systems;

UBI is one of the most urgent topics on political agendas, but it cannot be a remedy for mass automation of jobs;

Automation can be “right” if aimed at replacing risky jobs while creating opportunities for highly productive (or green) new jobs.

Alternative perspectives

🛑 On ProMarket, Sandeep Vaheesan, legal director at the Open Markets Institute, argues that, over the years, American antitrust has been negatively affected by the influence of neoclassical economic thinking, which is not rooted to reality. Economists still have a role in antitrust, but their research should be linked with the most pressing issues of our time, like income inequality and corporate power.

The theory in support of corporate consolidation appears shaky once a few basic questions are raised. Why assume that consumers are the only worthy beneficiaries of merger law and, contrary to congressional intent, ignore or discount the interests of workers, small firms, and competitors? Why presume that firms pursue mergers to become more productive? What about the pursuit of increased pricing power? After all, businesses do collude with each other. If greater pricing power is the goal, buying out a rival and centralizing control is more effective than trying to establish and maintain a price-fixing arrangement with the rival, which can balk or cheat so long as it remains independent. Why do firms need to buy out competitors, distributors, and suppliers to achieve scale and other productive efficiencies, when they can hire more workers and invest in new plant and facilities? And what about other rationales for mergers, such as the social prestige that comes with being the chief executive or chair of a very large corporation? These important questions are generally ignored in debates among antitrust insiders.

⚖️ In a new blog post on Le Monde, French economist Thomas Picketty argues that it is possible to restructure the current development model to make it more equitable and sustainable. The huge spending required for such a transformation could only be financed by debt. In the EU, this should take the form of mutual debt instruments with a single interest rate (Eurobonds) aimed at financing a green and social economy.

There must be a clear change in priorities and a certain number of taboos in the monetary and fiscal sphere must be challenged. This sector must work to the benefit of the real economy and used to serve social and ecological goals. In the first instance, we must use this forced shutdown to re-start on a different footing.After a recession of this type, the public authorities are going to have to play a pivotal role to restore growth and employment. But this has to be done by investing in new sectors (health, innovation, the environment) and by deciding on a gradual and lasting reduction in the most carbon-creating activities. In material terms, millions of jobs have to be created and salaries raised in hospitals, schools and universities, thermal renovation of buildings, community services.

🌎 In the last issue of The New Philosopher (Making the world whole again, p. 85), André Dao explains why it is so difficult to estimate the magnitude of the responsibility for climate disasters and their economic value. However, it is fundamental that those who are responsible for these disasters are held accountable by the international community.

Who is responsible for this catastrophe? The answer is pretty obvious: the rich. But that obvious answer is all too often obscured by phrases like “man-made” climate change, which imply that responsibility lies with humanity in general. According to Oxfam, the world’s richest 10 per cent account for 49 per cent of consumption-based emissions. […] Apart from the difficulty of calculating the amount of compensation,the necessity of translating loss into dollars distorts law’s perception of harm. […] Rather than thinking of responsibility as compensation, we could also think about responsibility as care. To put it simply, those who are most responsible for climate change should be responsible for looking after those most affected. That means not only stopping ongoing climate change by getting to zero emissions, but caring for the people for whom zero carbon targets in 2050 will be too late […].

Other readings

🔪 On The New Yorker, Eliza Griswold explains how and why the coronavirus emergency is heavily damaging the middle class.

📃 What if AI could design new economic policies? According to the MIT Technology Review, artificial intelligence could help to design fiscal policies that balance the need for economic equality and the willingness to invest.

🧨 According to Bloomberg, artificial intelligence and 5G communication technologies will be at the core of South Korea’s New Deal, a plan to finance the recovery of the economy through public spending.

📈 The Wall Street Journal lists six interesting theories on why fast-growing startups are not anymore a mainstream phenomenon.

🤝 Microsoft and Oracle are secretly allied to prevent Amazon from becoming the leader tech behemoth; a primer of this alliance took place within the JEDI contract with the Pentagon, awarded by Microsoft (The Information).

🆘 On Science, Lizzie Wade analyzes how, also in past pandemics, the weakest members of society have suffered the most from social and economic consequences.

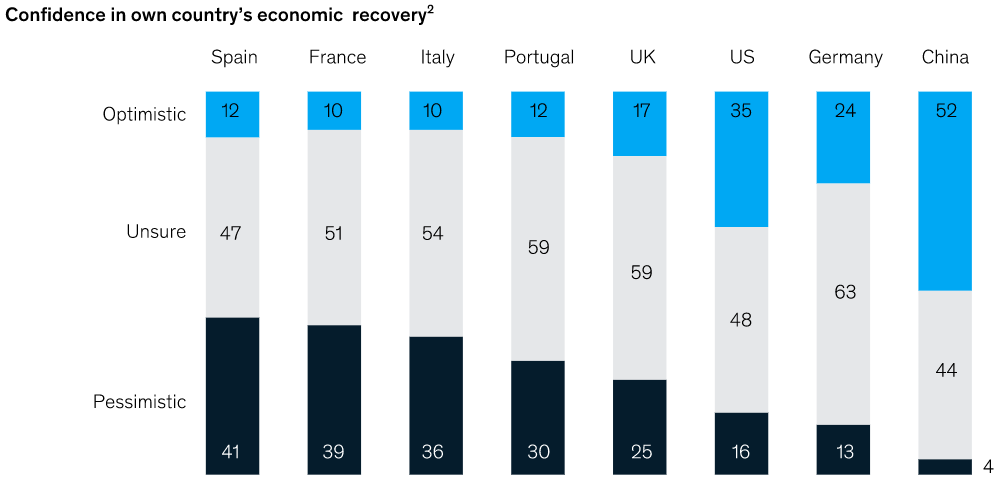

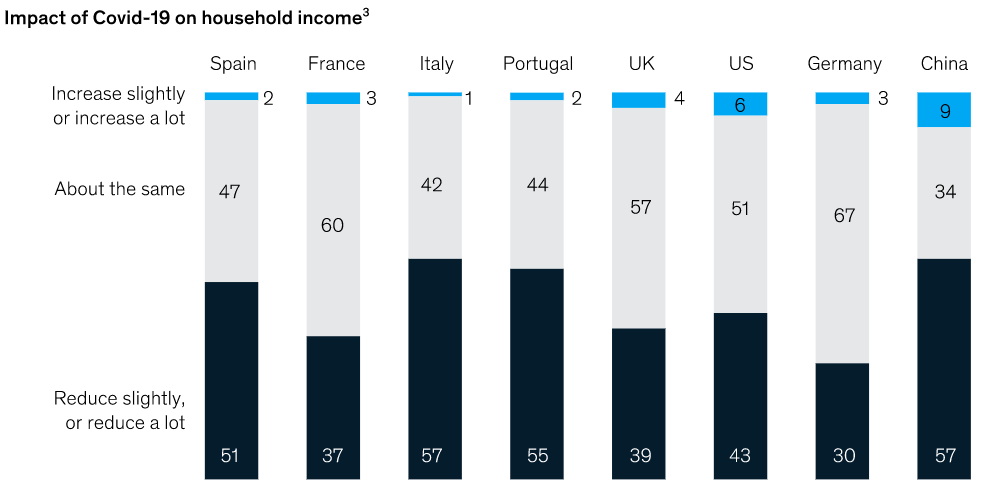

📊 In a new report by McKinsey, the confidence in economic recovery and the impact of COVID-19 on household income are compared for different countries. The Chinese optimism about the recovery is extremely interesting.

Thanks for reading.

Please give me any feedback about this issue. If you enjoyed reading it, like and share Reshaped with potentially interested people.

Have a good weekend!

Federico